|

| Kievan Rus |

Kievan Rus (860s–1238), the first state of the Eastern Slavs, received its name from its capital city Kiev, located along the middle Dniepr River (modern Ukraine).

Founded and ruled by the Riurikid princes, during its height in the 11th and 12th centuries Kievan Rus spanned most of modern Belarus and

Ukraine, extending northward to the Republic of Novgorod, which controlled lands extending from the Baltic to the White Seas and the northern Ural Mountains.

The medieval state stretched across four latitudinal landscape zones, each favorable for different forms of economic exploitation:

tundra (hunting-gathering), boreal forest and intermediate forest-steppe (hunting-gathering and agriculture), and the steppe (pastoral nomadism).

The Western Dvina, Volkhov-Lovat, Dniepr, and Volga river systems linked these diverse resource zones. It was the economic and political unification of these territories that made Kievan Rus one of the wealthiest and most cosmopolitan kingdoms in medieval Europe during the 11th and 12th centuries.

The history of Kievan Rus is best divided into three developmental periods: foundation period (750s–988), the golden age (988–1050s), and fragmentation into principalities (1050s–1238). Mongol armies under Batu Khan brought the period to its end with the destruction of Kiev, Riazan, Vladimir, and many other towns from 1237 to 1239.

Foundation Period The main written account for the foundation period is the

Russian Primary Chronicle, compiled by monks at the Kievan Caves Monastery in the early 12th century. Archaeological and numismatic evidence serves as a supplement and corrective to this problematic account.

These sources trace the early formation of the Rus lands to the Volkhov-Il’men river basin of northwestern Russia. Finno-Baltic hunter-gatherers inhabited this densely forested marshy region.

In the mid-eighth century Slavic agriculturalists began migrating to the area from the south. At the same time Scandinavians began small-scale raiding/trading expeditions to the region. The convergence of these groups served as the initial catalyst for the development of a new political-commercial community.

Forces at play in both northwestern Europe and the Middle East explain Scandinavian movement into Russia. Lacking locally exploitable sources of silver, which was needed for northwestern European political and commercial expansion, the early medieval kingdoms of the Anglo-Saxons and Franks looked to the Near and Middle East, where, from the mid-eighth century, the Abbasid Caliphate centered in Baghdad minted millions of silver coins (dirhams) annually.

The

Vikings acted as the middlemen for this trade. Beginning sometime in the mid- to late-eighth century, small groups of Vikings set up way stations in the Volkhov-Il’men and Upper Volga basins.

They collected furs from the Finno-Balts and Slavs in northwestern Russia and sailed south to trading ports on the Volga River and Caspian Sea, where they would exchange furs, Frankish swords, and walrus ivory for eastern luxury items, especially silver.

|

| confederation of Slavs and Finns invited the Viking Riurik |

According to the Chronicle, in 859 the Vikings were expelled from Russia by the local tribes, probably for taking excessive tribute, but three years later in 862 a

confederation of Slavs and Finns invited the Viking Riurik and his clan “to come and rule over them.”

Establishing a base first at Staraia Ladoga and then Riurikovo Gorodishche, Riurik proceeded to create tributaries of the Slavic tribes to the west, in Pskov, and to the northeast in Beloozero.

After his death in 879 his kinsman Oleg seized Kiev, thereby assuming control over the tributary relationships with nearby tribes previously exploited by the Khazar empire. By the late 10th century the Riurikid clan, which had become increasingly Slavicized through marriage, had subjected all of the Slavic and Finnic tribes to their rule.

The foreign policy of the Riurikids was directed toward creating stable commercial relations with one of the largest markets in the known world, the

Byzantine Empire.

From 860 to 1043 the Vikings (and later Slavicized Riurikids) attacked the Byzantine Empire six times (860, 907, 941, 944, 971, and 1043). Most of the campaigns resulted in commercial treaties regularizing trade between Kievan Rus and

Constantinople.

Each year the Riurikids spent the winter collecting tribute from subject tribes, and in the spring the commercial delegation sailed to Constantinople, where it spent the

summer trading their furs, honey, wax, and slaves for Byzantine finery (glass, jewelry, hazelnuts, spices).

Commercial contact with the Greek empire via the so-called road from the Varangians to the Greeks helped introduce the Eastern Slavs to Greek culture, diplomacy, and religion.

In 955 Grand Princess Olga converted to Byzantine Christianity. Her son, Sviatoslav (d. 972), a committed pagan who was more interested in war than diplomacy, waged an unsuccessful campaign to capture Byzantine Bulgaria and was killed by nomadic Pechenegs in the Byzantine hire.

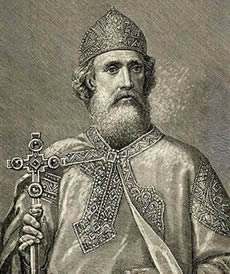

His son,

Vladimir I (Vladimir the Great) (d. 1015), was a champion of Slavic paganism as well, but he recognized the problems inherent in Kiev’s increasing religious isolation from its neighbors.

While the Rus considered converting to Islam, they chose instead Byzantine Christianity. Vladimir was baptized in 988 and married the sister to the Byzantine emperor, Anna, an incredible honor for a “barbarian” from the north.

This move forged an enduring relationship between the Eastern Slavs and Byzantines, with Rus princes providing goods of the north and military assistance to Constantinople in exchange for Greek cultural and religious knowledge, including a written script (Cyrillic), church architects, clergy, and craftsmen (mosaicists, glassmakers, icon painters, manuscript copyists).

Golden Age  |

| Kievan Rus map in 11th century |

Vladimir’s son,

Yaroslav the Wise (c. 980–1054), is credited with the golden age of Kievan Rus. He created foreign alliances by marrying Ingegerd, the daughter of the Swedish king, and marrying his daughters to German and French kings.

Under his reign Kiev’s buffer zone separating it from the Pechenegs expanded from a one- to a two-day march. Yaroslav sponsored major building campaigns in Kiev, which imitated the architecture of Constantinople. He imported Byzantine master builders who constructed the Church of St.

Sophia of Kiev (which was decorated by Byzantine mosaicists), the Golden Gates, a palace, and a massive defense works surrounding the capital. In order to support Kiev’s new religion, Yaroslav founded monasteries and invited Greek clergy to Kiev, who taught Byzantine religious practices to the native and often illiterate clergy.

In 1051 Yaroslav appointed the first native metropolitan, which helped establish the Russian church’s autonomy from Constantinople. He also commissioned the first Church Statute and the first Russian law code, the Russkaia Pravda.

In a testament left to his sons, Yaroslav tried to establish an order of succession, with the oldest son, Iziaslav, ruling Kiev, and the younger sons appointed to cities of importance commensurate to their place in the line of succession.

When an older prince died, the younger moved up the line of succession and to larger and more lucrative towns. The inheritance tradition of Kievan Rus was one of lateral succession, with brother succeeding brother.

The system, however, promoted acrimony during the lifetimes of Yaroslav’s sons, and the duduk perkara increased as family lines multiplied. Vladimir Monomakh (1053–1125), the grandson of Yaroslav the Wise, was the last Kievan monarch to exercise any real authority over much of Kievan Rus.

Vladimir derived much of his authority from his ability to lead his cousins in several successful campaigns against the Polovtsian nomads, who had terrorized the kingdom’s southern frontier, including Kiev itself, from the second quarter of the 11th century.

Fragmentation Into Principalities Evidence suggests that during the 12th century, Kiev entered a period of decline, a theory that is contradicted by archaeological evidence of burgeoning industrial production and continued commercial relations with Constantinople. However Kiev’s political sway over the kingdom dissipated with the growth of other Rus towns.

The towns of Vladimir-Suzdal, Polotsk, Pskov, Smolensk, Pereiaslavl, Turov, and Chernigov were ruled by branches of the Riurikid family who had come to view these towns and their hinterlands as their patrimonies absolutely independent from Kiev.

To promote their legitimacy, the rulers of these towns built stone churches and palaces modeled after those in Kiev. They sponsored the foundation of monasteries and commissioned the monks to write detailed chronicles of their family’s branch of the Riurikid dynasty and the history of their town.

In addition to master builders they imported master craftsmen from Kiev, who established workshops in their new towns specializing in the manufacture of glass bracelets, jewelry, textiles, and other Kievan-Byzantine luxuries.

In this way Kievan-Byzantine culture came to dominate throughout much of the Rus principalities, homogenizing the Eastern Slavic lands by spreading an elite culture through its cities. Local cultural forms developed as well during this period, with icon painting schools emerging in Pskov, Novgorod, and Vladimir-Suzdal.

An alternative to the pattern of centralized princely rule established in Kiev and followed by the independent principalities was the city-state of Novgorod. Founded in the mid-10th century, Novgorod was the second largest city of Kievan Rus, and possibly wealthier, because of its importance as medieval Europe’s key source of furs. Because of its wealth and status, the Kievan princes treated Novgorod in a special manner, appointing their eldest sons or close associates to rule the town.

In 1136 Novgorod’s

population expelled their prince and claimed the right to choose from any branch of the Riurikid clan. The prince protected the town and received revenues from its trade but had to reside beyond the town walls.

The town assembly (veche), governor (posadnik), and archbishop became major determinants in Novgorod’s administration. These principal actors in Novgorodian politics had the power to remove the prince. Because it was located so far to the northwest, Novgorod was one of the few towns not touched by the Mongol invasion.

In the 14th and 15th centuries Novgorod became one of the most powerful states in Europe, serving as one of the Hanseatic kontor. In 1478 the grand prince of Moscow annexed Novgorod and cut one of the main sources of its revenue when, in 1494, he closed Peterhof.

Although Kievan Rus comes to its official close in 1237–39 with the Mongol invasion, there were signs of weakening beforehand. Already in the early 12th century, the Swedish kingdom began militarily driven efforts to convert the Eastern Slavs in the Novgorod lands to Latin Christianity.

Crusading campaigns fought by German knights gained momentum during the 13th century under the organization of the Teutonic Order in Livonia. Although not in danger from the northern crusades, Kiev became the victim of the southern crusades when, in 1204, an army of crusaders seized and sacked Constantinople, holding the Byzantine capital until 1261.

Heavily dependent on trade with Constantinople, Kiev entered upon a long period of economic depression, which contributed to its weakened defenses, which were ill equipped to organize a resistance the Mongol army in 1238. In 1223 several Rus princes fought a small Mongol army, which turned out to be a scouting party, on the river Kalka.

While the Russian sources attribute the Rus princes’ inability to defend Rus in the late 1230s to political infighting and lack of Christian brotherhood, it is doubtful that even an army united under all of the surviving Riurikids could have defeated Batu Khan’s army of more than 150,000 horsemen.