Zimbabwe, or Rhodesia, as it was known until 1980, is a landlocked nation of 13 million people occupying the plateau between the Limpopo and Zambezi Rivers, bordered by Zambia to the north, Botswana to the west, Mozambique to the east, and South Africa to the south.

While the rest of Britain’s African colonies, including two of Rhodesia’s neighbors—Northern Rhodesia (Zambia) and Nyasaland (Malawi)—gained independence as part of a wave of decolonization, Rhodesia remained a bastion of minority white rule because of its influential European population. Even after the country gained majority rule in 1980, white control of land continued to be a crucial issue in Zimbabwe.

At midcentury, mostly because of the country’s substantial mineral wealth and fertile soil for tobacco cultivation, Rhodesia’s white population enjoyed one of the highest standards of living in the world.

The country’s black residents, however, who made up over 95 percent of the population, possessed little political power and received just 5 percent of the nation’s income. Having gained control by force roughly a half-century earlier, whites made up one-twentieth of the population but held one-third of the land.

At the end of

World War II the political winds began to change. Britain moved to grant independence to many of its colonies in Asia and Africa. Rhodesia, which had been a British-chartered corporate colony at the turn of the century and a self-governing British colony since 1923, took on a new political form in 1953 with the establishment of the Central African Federation. Southern Rhodesia dominated this confederation; it exploited the copper of Northern Rhodesia and the labor of Nyasaland.

The arrival of independent rule in Northern Rhodesia (Zambia) and Nyasaland (Malawi) in 1964 brought considerable anxiety to the white population of Southern Rhodesia, who believed that Britain favored majority rule.

In response, in November of 1965, Ian Douglas Smith, an unabashed champion of white rule, announced the Unilateral Declaration of Independence, which cut the country’s ties with Britain and established the independent nation of Rhodesia. In a referendum, overwhelming numbers of the white population supported Smith. Britain responded by imposing diplomatic and economic sanctions.

The cold war struggle between the United States and the

Soviet Union for influence around the world, including in the nations of Africa, complicated these developments. U.S. relations with Ian Smith’s white-ruled Rhodesia at the time shows the ambivalent position of the United States.

On the one hand the United States valued the support of Rhodesia, which contained vast reserves of strategic minerals, especially chromium, and adopted a strongly anticommunist stance. Yet, at the same time, the United States worried that support for Smith’s white supremacist government would cost it needed friends in rapidly decolonizing Africa.

In 1965 U.S. president

Lyndon B. Johnson condemned Smith’s unilateral declaration of independence and, following Britain’s lead, imposed economic sanctions. Although these sanctions could have been even stronger, U.S. trade there declined from $29 million in 1965 to $3.7 million in 1968, a real blow to the Rhodesian economy. At the same time, though, Rhodesia received substantial support from some within the United States.

The Byrd Amendment of 1971, which was enacted with the support of the

Richard Nixon administration, punched a significant hole in the sanctions against Rhodesia. According to this law, the United States could not ban the importation from a non-communist nation any material needed for national defense if that same material would otherwise be purchased from a communist nation.

Since chromium, a key resource for many modern weapon systems, was also imported from the Soviet Union, the United States was forced to allow trade with Rhodesia. Imports of chromium grew from $500,000 in 1965, to $13 million in 1972, to $45 million in 1975.

Organized black resistance to white rule in Rhodesia took shape in the late 1950s, and the two main oppositional parties, parties that would dominate Zimbabwean politics well beyond independence, were established in the early 1960s.

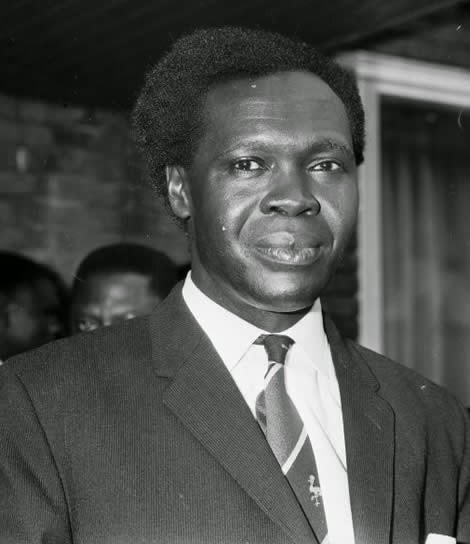

In 1957 the African National Congress, based in Bulawayo, and the African National Youth League, based in Salisbury (present-day Harare), combined to form the Southern Rhodesian African National Congress under Joshua Nkomo. Banned in 1959, this group was succeeded by the National Democratic Party, which was itself banned in December 1961.

Shortly thereafter, the Zimbabwe African People’s Union (ZAPU) was established. A major split occurred in 1963, resulting in the formation of the Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU). ZAPU was mostly Ndebele and Chinese-leaning; ZANU was mostly Shona and Soviet-leaning.

ZAPU and ZANU adopted different strategies at different times. During the 1960s, as white Rhodesians like Ian Smith grew more extreme, African nationalist methods became more militant and confrontational.

Both ZANU and ZAPU began attacking white farms in 1964, but they quickly realized they were outmatched by the Rhodesian military. A more moderate group, the African National Council—organized by Bishop Abel Muzorewa—sprang up during the early 1970s. None of these groups had much

success.

The situation began to shift during the late 1970s. In 1975, after long wars, two Portuguese colonies in southern Africa, Mozambique and Angola, gained their independence. Black-ruled Mozambique became a safe haven for many of the guerrilla groups opposing the white regime in Rhodesia. In 1975 the two most important of these groups—ZANU, under Robert Mugabe, and ZAPU, under Joshua Nkomo—joined forces to become the Patriotic Front.

Jimmy Carter’s victory in the U.S. presidential election of 1976 also played a role in shifting the context of Rhodesian politics. Concerned about the U.S. reputation in other parts of black Africa, the Carter administration began to push for a settlement to the conflict. In general, the United States supported majority rule with protection of white interests.

The British called the Lancaster House Conference in an attempt to broker a lasting solution. The resulting settlement guaranteed majority rule for Zimbabwe, a transitional period for whites, and a multiparty system.

At the center of the settlement was a new constitution, which gave the vote to all Africans 18 years and older, reserved 28 seats in the parliament for whites for 10 years, and guaranteed private property rights. In the election of February 1980, voting mostly followed ethnic lines. ZANU–Popular Front won a clear majority, making its leader,

Robert Mugabe, the prime minister.

ZAPU–Popular Front, which had recently split from ZANU-PF, joined the white members of parliament in opposition. Taking its name from the 14th- and 15th-century stone city of Great Zimbabwe, Rhodesia became Zimbabwe on April 18, 1980. The war for majority rule, which had cost over 25,000 lives, most of them black, was over.

Under Robert Mugabe’s rule, Zimbabwe in the 1980s pursued socialist-leaning policies not unlike those of many other countries in Africa. It expanded social programs that had been denied under white rule. And, although it claimed to want to redistribute land, in reality it moved slowly to break up successful white farms.

This cost the regime politically but it enabled Zimbabwe to continue to feed itself. Overall, during the early 1980s many Zimbabweans saw real improvements in the

quality of their lives.

As the 1980s unfolded, Mugabe began to show authoritarian tendencies. Even early on he rounded up opponents, censored the press, and gave broad authority to security forces. At first he was able to get away with this because of his wide support, especially in rural areas.

Mugabe won the March 1996 election with 92.7 percent of the vote, but only a very small number of Zimbabweans bothered to vote. The decrease in voter participation revealed the growing discontent of Zimbabweans with Mugabe. On top of this, in the early 1980s a civil war that would last until 1987 broke out in Matabeleland, a stronghold of the ZAPU-PF.

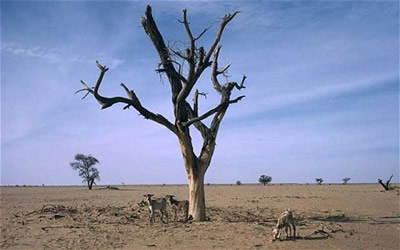

In the late 1990s Mugabe initiated two very controversial programs. In 1997, he began seizing white-owned land without compensation and quietly encouraging landless blacks to move onto white farms. These farms had previously fed the nation and provided work for large numbers of people, mostly black.

In 2002 Mugabe appropriated the remaining white land and ordered white farmers to offer payments to former workers. Because many of the blacks who moved onto the white land had few farming skills, the nation soon faced a food crisis.

Critics, moreover, claimed that Mugabe handed out the best land to his family, friends, and close supporters. In another controversial move, in 1998 Mugabe deployed the military in the Democratic Republic of the Congo to help its government fend off an armed rebellion.

The situation in Zimbabwe seems precarious. During the 2002 elections Mugabe rigged the voting and jailed opponents, especially the supporters of the Movement for Democratic Change, led by Morgan Tsvangirai. Neighboring nations supported Mugabe but other African nations, such as Kenya and Ghana, condemned his move.

Famine conditions persist in Zimbabwe, and the people struggle with skyrocketing prices and extremely high unemployment. That no system is in place to determine a successor to the aging Mugabe portends a divisive struggle to come.