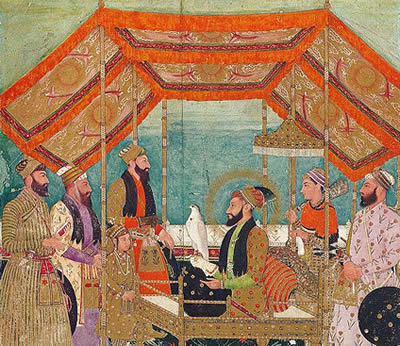

At the age of 23, Humayun succeeded his father, Babur, as the second Mughal ruler of India. He ruled successfully for the first few years, then abandoned himself to pleasures, including use of opium, resulting in the loss of his patrimony to Sher (Shir) Shah and years of wandering and exile in Persia. He was finally restored to power in India with Persian help in 1555 but died from a fall in 1556.

Humayun inherited a shaky empire that had just been conquered by his father, and he had to deal with three ambitious brothers eager to oust him. Although capable of courage, he was self-indulgent and addicted to pleasures. Two enemies confronted him after his accession, Sultan Bahadur in the southwest and Sher Khan (later titled Sher Shah), leader of Afghans who had settled along the Ganges River in Bihar.

Sultan Bahadur was eliminated by the Portuguese but the more able Sher Khan decisively defeated him in 1539. He was forced to flee with few followers across India, to Afghanistan, finally finding refuge in Persia, whose ruler Sha Tahmasp gave him refuge on condition that he converted to the Shi’i (from Sunni) Islam. He did so, at least outwardly.

The victorious Sher Khan assumed the title of shah and very ably ruled India from 1540 to 1545. He built up an excellent administrative system, which became the foundation of the later resurrected Mughal Empire. He relied on centrally appointed local officials who administered under a hierarchical system of responsibility. Local officials assessed and collected taxes, at one-third of the total production.

He set up courts and weeded out corrupt and oppressive officials. He also established charitable organizations to help the poor and built roads shaded with trees and with rest houses and wells for drinking water interspersed along the way. He died in 1545, when a gunpowder magazine accidentally exploded.

Sher Shah’s sons lacked his ability and made matters worse by fighting with one another for their inheritance. Thereupon Sha Tahmasp helped Humayun return to power, first conquering Kandahar and Kabul in Afghanistan, and then winning back his throne in India in 1555.

He died the following year, however, after a fall in his palace, leaving the throne to his 13-year-old-son, Akbar, born on the northwestern frontier of India during his father’s desperate flight. Babur founded the Mughal Empire, Sher Shah laid its administrative foundations, and Akbar later consolidated it.

Humayun inherited a shaky empire that had just been conquered by his father, and he had to deal with three ambitious brothers eager to oust him. Although capable of courage, he was self-indulgent and addicted to pleasures. Two enemies confronted him after his accession, Sultan Bahadur in the southwest and Sher Khan (later titled Sher Shah), leader of Afghans who had settled along the Ganges River in Bihar.

Sultan Bahadur was eliminated by the Portuguese but the more able Sher Khan decisively defeated him in 1539. He was forced to flee with few followers across India, to Afghanistan, finally finding refuge in Persia, whose ruler Sha Tahmasp gave him refuge on condition that he converted to the Shi’i (from Sunni) Islam. He did so, at least outwardly.

The victorious Sher Khan assumed the title of shah and very ably ruled India from 1540 to 1545. He built up an excellent administrative system, which became the foundation of the later resurrected Mughal Empire. He relied on centrally appointed local officials who administered under a hierarchical system of responsibility. Local officials assessed and collected taxes, at one-third of the total production.

|

He set up courts and weeded out corrupt and oppressive officials. He also established charitable organizations to help the poor and built roads shaded with trees and with rest houses and wells for drinking water interspersed along the way. He died in 1545, when a gunpowder magazine accidentally exploded.

|

| Humayun tomb |

Sher Shah’s sons lacked his ability and made matters worse by fighting with one another for their inheritance. Thereupon Sha Tahmasp helped Humayun return to power, first conquering Kandahar and Kabul in Afghanistan, and then winning back his throne in India in 1555.

He died the following year, however, after a fall in his palace, leaving the throne to his 13-year-old-son, Akbar, born on the northwestern frontier of India during his father’s desperate flight. Babur founded the Mughal Empire, Sher Shah laid its administrative foundations, and Akbar later consolidated it.