|

| Umayyad Dynasty at its greatest extent |

After Ali’s death and his son Hasan’s renunciation of the caliphate, Muaw’iya became the undisputed caliph of the Muslim world in 661. He established a hereditary dynasty with Damascus as its capital.

However, unlike in most western monarchies, succession was not based on primogeniture; the ruler selected anyone within his family as the chosen heir. However, the undisputed claim of the Umayyad family to the caliphate was short lived.

When Muaw’iya died in 680, his son Yazid’s claim to the position was immediately challenged by Ali’s younger son Husayn. Yazid’s forces inflicted a stunning defeat over Husayn and his Shi’i followers at the Battle of Kerbala but the victory was bittersweet as it resulted in the permanent division of the Muslim community into the orthodox, majority Sunnis, who accepted the legality of the Umayyad rule, and the Shi’i, who did not.

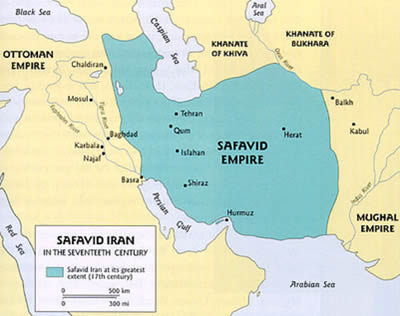

Internal divisions, especially from Iraq and Khurasan, an eastern province of the old

Sassanid empire in Persia, were persistent problems during the Umayyad reign.

The Umayyads appointed Hajjah ibn Yusuf al-Thaqafi to control the rebellious provinces of Iraq and he was fairly successful in putting down the sporadic, but persistent rebellions. He was responsible for appointing governors for Khurasan as well.

In the first years of the empire the administration was fairly decentralized and Greeks and Copts held many major bureaucratic positions. Muslim judges (qadis) were appointed but they dealt only with the Muslim population. The majority non-Muslim population retained their own communal systems.

|

| Umayyad Mosque in Damascus |

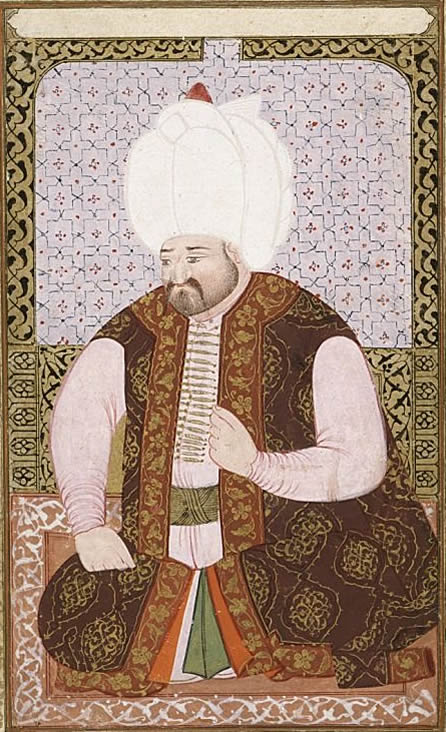

Under Abd al-Malik (r. 685–705), the Umayyad empire became more highly centralized. He established a national mint and the process of Arabization of the vast Umayyad territory spread as Arabic became the lingua franca of the empire. Arabic became the language not only of Islam but of trade and government.

Provincial governors were appointed to administer the far-flung territories but when the caliphs were weak and central control lessened, these governors often became political powers in their own right.

The boundaries of the empire continued to widen as Abd al-Malik personally led his troops into battle. His able commander Hasan ibn Nu’man took Tunis in North Africa in 693; the Berber population subsequently converted to Islam and was largely responsible for the spread of the faith into Spain.

Abd al-Malik also paid for the construction of the Dome of the Rock mosque in Jerusalem. Built on the site where Abraham was willing to sacrifice his son Isaac, it was also the site of Solomon’s temple and the prophet Muhammad’s miraculous ascent into the heavens.

Muslims referred to the site as the Haram as-Sharif (Sacred Mount), while it was known as the Temple Mount to Jews. Thus the site had holy meaning for all three great monotheistic religions.

Completed in 692 the Dome of the Rock remains one of the most notable architectural achievements of the Arab/Islamic empire. The great Umayyad Mosque in Damascus was completed in 705. Essentially secular rulers the Umayyads also built numerous fortresses and hunting palaces.

|

| Dome of the Rock, Masjid Al-Aqsa |

The Umayyad empire reached its furthest geographic limits under Caliph al-Walid (r. 705–715). The Berber commander al Tariq led Muslim forces across into Spain in 711 and established a foothold at Jabal Tariq or Gibraltar. To the Arabs, the Spanish province was known as al-Andalus, or land of the Vandals.

Within a few years Muslim armies had moved across the Pyrenees into France. Muslim armies were halted in 732–733 by Charles Martel at the Battle of Tours, marking the farthest point of Muslim conquests in western Europe.

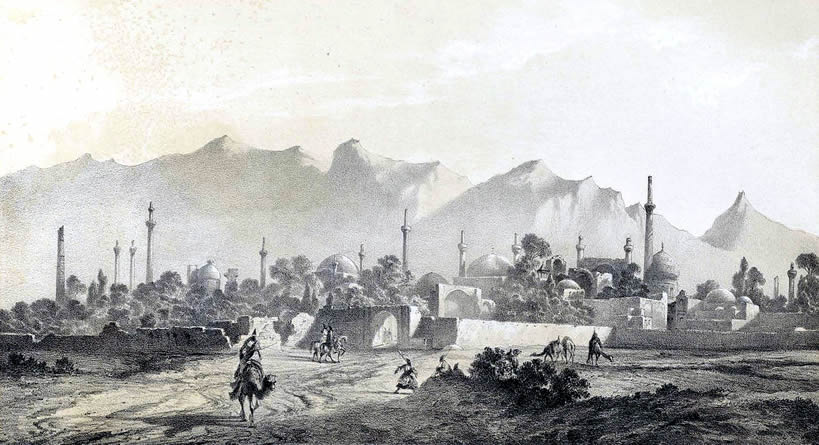

In the east, Muslim armies conquered Afghanistan and territory across the Indus River deep into India, where they made numerous converts among the

Buddhist population. Attempts in 670 and subsequently to take the Byzantine capital

Constantinople all failed and the Byzantine Empire was able to survive until the 15th century.

In contrast to his predecessors, Caliph Umar II (r. 717–720) was known for his religious piety. He proclaimed the equality of all his subjects, Muslims, Arabs, or non-Muslims, but he also established some differentiations based on dress whereby Christians were forbidden to wear silk garments or turbans in public.

The collection and distribution of tax revenues were a perennial dilema for the Umayyads. Provincial governors were often reluctant to send monies to the state, preferring to spend revenues in their own localities. The Umayyads never established an effective centralized means of fiscal control.

Under Islamic law the non-Muslim population had not been forced to convert and non-Muslims or Dhimmis remained the majority of the population throughout most of the empire. Dhimmis paid land tax in addition to a poll tax from which Arab Muslims, the original conquerors, were exempt. In addition Muslim Arabs also received a state stipend.

As more non-Arab subjects converted to Islam, revenues flowing into the central treasury decreased. The Umayyads attempted to replenish revenues with ambitious land reclamation and irrigation schemes to increase agricultural productivity.

The revenues from these projects went to the state. Under Caliph Hisham (r. 724–743) land tax was to be paid whether one had converted or not, although converts did become exempt from the poll tax.

The non-Arab Muslim population was gradually absorbed into society although the social cleavages between the elite Arab population, represented by the Umayyads, and more recent converts remained. Slaves were at the bottom rung of the social and economic strata. Most slaves were acquired as property in wars, but some were purchased through

slave trading.

By the eighth century the Umayyads faced mounting economic problems. Revenues for the state and its huge army declined as conquests largely ceased. Unpaid soldiers posed a constant dilema of rebellions in the provinces.

In its tanggapan years the Umayyad Empire was also plagued with internal problems over succession to the caliphate. In 750 the Umayyads lost a major battle to the rebellious Abbasids, who enjoyed support from the Khursasan province. The caliph Marwan fled to Egypt but was pursued and killed.

Except for Abd al-Rahman most of the Umayyad family was also assassinated. Abd al-Rahman managed to escape and established an Umayyad dynasty in Córdoba, Spain. With the end of the Umayyad dynasty a new Muslim elite of Persian and then Turkish origins emerged under the Abbasid empire.

Although it had been built on Islamic conquests, the Umayyad Empire was essentially a secular dynasty. Umayyad rulers, with the exception of the pious Umar II, were known for their lavish secular lifestyles and sumptuous courts.

They were pragmatic rulers who opposed those who wanted to establish a religious state. Under the Umayyads, Dar al-Islam (House of Islam) was a confident, largely self-sufficient empire that covered vast territories made up of many diverse peoples.