|

| Koryo Dynasty |

The kingdom of Koryo (or Goryeo) in Korea was named after the dynasty that ruled from the fall of the

Silla dynasty in 935 c.e. until the Yi dynasty overthrew it in 1392. The English name Korea is derived from the word Koryo. The kingdom of Koryo was an empire until it was forced to take the status of a kingdom when dealing with the

Yuan dynasty (1279–1368) in China.

The kingdom of Koryo traces its origins back to the weakening of Silla during a civil war in the early 10th century. Major rebellions against the Silla rulers had been led by Kung Ye, Ki Hwon, Yang Kil, and Kyon Hwon, with Kung Ye forming the kingdom of Hugoguryo (the Later Kingdom of Koguryo) and Kyon Hwon establishing Hubaekje (the Later Kingdom of Paekche). It was the first of these, the Later Kingdom of Koguryo, that would emerge as the kingdom of Koryo.

When Kung Ye led his rebellion against Silla, he wrested from their nominal control much of central Korea and established his capital at Kaesong (Songak) in 901. Soon afterward another rebel, Wang Kon (or Wanggeon, or Wang Kien), emerged to help the rebellion.

He was from a merchant family and drew support from nobles who had watched the stagnation of the Silla with horror. Kung Ye recognized the leadership qualities of Wang Kon and appointed him the prime minister of the new government based at Kaesong.

However in 918 Wang Kon overthrew Kung Ye and placed himself at the head of the rebellion. Wang Kon obviously realized that even though the Silla were weak, he did not initially have the military force capable of defeating them. As a result it was not until 934 that Wang Kon decided to attack the Later Kingdom of Paekche at Hongson (Unju).

Wang Kon’s victory was quick because in 935, Kyon Hwon surrendered to him. The Later Paekche king had designated his fourth son as his heir and this had annoyed his eldest son, Sin-gom, who drove him from the kingdom. Wang Kon easily overcame Singom’s army and the Later Kingdom of Paekche became a part of the emerging kingdom of Koryo.

In December 936 the Silla king, Kyongsun, realizing that his forces would be unable to defeat Wang Kon in battle, also surrendered and Wang Kon became the king of the Korean Peninsula, ruling from Kaesong.

Wang Ko, better known by his posthumous title, King T’aejo, decided to be magnanimous and gave exking Kyongsun the highest position in his new government, marrying a daughter of one of the Silla rulers, which helped legitimize his rule in the minds of many nobles.

Furthermore he left most of the nobles in charge of their lands. When he died, after a reign of only seven years, his son became King Hyejong (r. 943–945), and succession was unchallenged. For many people, their connection with the court was through a

Buddhist hierarchy that controlled much of the countryside.

The first external challenge faced by the new Koryo dynasty was a series of invasions by the Khitan peoples to the north and the west of Korea. They controlled many of the lands on the north of the Yalu Rover and claimed to be descendants of the original leaders of Korea.

|

| koryo army |

The Koryo tried initially to conclude an agreement with the Khitan but soon realized that this tribe actually wanted nothing less than control of most of the Korean Peninsula. In China, the new

Song (Sung) dynasty was entrenching itself in power and sought an alliance with the Koryo.

Realizing that they would soon have enemies on both sides of them, the Khitan attacked in 983, 985, and 989 in a series of raids across the Yalu River. They decided to invade the Korean Peninsula before the Chinese could conclude an alliance with Koryo, and in October 993 a large Khitan army, estimated by some historians as being 800,000, led by Hsiao Sun-ning, attacked Koryo.

The Koryo king, Songjong, took command of his soldiers at Pyongyang and held up the Khitan advance. Recognizing that the Khitan would not be able to win a long and protracted war in enemy territory, the Khitan negotiated a peace agreement and withdrew.

A similar persoalan arose in 1115 with the Jurchen (Manchu) tribe in Manchuria. The Jurchen leader had occupied southern Manchuria and proclaimed himself the emperor of China. They attacked the Khitan kingdom of

Liao, and with help from the Sung, managed to destroy the threat of the Khitans sacking Liao in 1125.

The Jurchen then attacked the Song, who were forced to retreat to southern China. With the Koreans uncertain who was going to win this war, and worried the Jurchen might become too strong and decide to annex Korea, the Koryo kings were more careful in not getting involved in the war in China.

In 1126 there was a major dispute over the focus of the kingdom. One group wanted to keep the capital at Kaesong and preserve the status quo. The other, led by Myo Cheong, wanted the capital moved back to Pyongyang, which would allow Korea to expand to the north.

In 1135 the Myo Cheong rebellion failed. However 35 years later Jeong Jung-bu and Yi Ui-bang launched a coup d’etat against King Injong, who was exiled, and Myongjong became the next king, reigning until 1197. For much of that time he was a puppet who served the interests of contending generals such as Kyong Taesung (r. 1177–84).

In 1197 Choi Chungheon, another general, deposed Myongjong, and replaced the king with Sinjong (r. 1197–1204). He then ousted Sinjong and put Huijong on the throne. However Choi Chungheon deposed Huijong in 1211, and a new king, Kangjong, ruled for two years. Choi found the next king, Kojong, more compliant, and he outlasted Choi, reigning until 1259.

In 1202 Genghis Khan was elected leader of the Mongols and attacked first the Jurchen and then the Chinese. Mongols chased some escaping Khitan refugees to Pyongyang and in 1279, having conquered China, established the

Yuan (or Mongol) dynasty, moving the capital of China to Beijing.

The Koryo kings decided not to challenge the power of the Mongols and tried to maintain some semblance of independence but at the same time dispatched tribute to the Mongols, sending royal hostages to Beijing, and some of the kings had to marry Mongolian women.

Three of the later Koryo kings, Chungnyol, Chungson, and Chungsuk, spent most of their time at the Mongol court, leaving little time to manage their own kingdom. It was a diplomatic balancing act but did ensure that the Mongols, with their well-known bloodthirst and penchant for revenge, did not pillage Korea in the way that other areas were destroyed by them.

However when the Mongol emperor of China

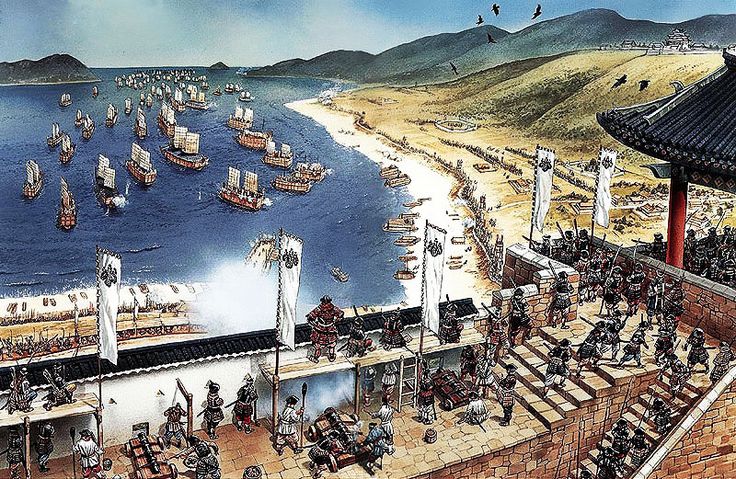

Kubilai Khan, wanted to attack Japan in 1274 and again in 1281, the Koreans had to provide many soldiers and use their manpower to build the Mongol navy. The first attack was launched from Happo (Masan) on the southern coast of Korea.

The fleet of 900 ships carrying 40,000 soldiers sailed to Tsushima and then onto Kyushu, where they fought the Japanese in Hakata Bay. The second invasion force, also including many Koreans, involved two fleets, one of which left from Korea—a total of 4,400 ships and 142,000 soldiers.

Tens of thousands of Koreans were killed by the Japanese during these futile attacks or died when the ships in both attacks were hit by freak typhoons With so many of the soldiers having been Korean levies, the loss struck a major blow against the Korean economy and on the Koryo dynasty, which had, in name, supported the attack.

Many of the later rulers of the Koryo dynasty were young, with six of the last nine being teenagers or younger when they became king. King Chunghye (r. 1330–32, 1339–44), and King U (r. 1374–88) spent most of their reigns chasing wild animals in hunts, being involved in drunken parties, or having affairs with countless women.

King Kongmin (r. 1351–74) was the only one of the latter Koryo kings who provided any stability to the country. However after the death of his wife, he spent much of his reign obsessed with finding an auspicious place for her to be buried, and where he could also be interred.

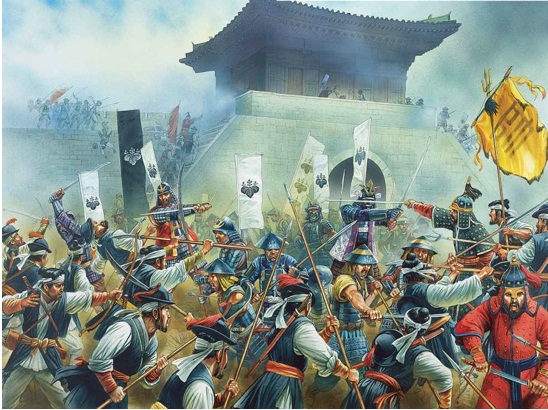

He eventually settled on a spot about nine miles west of Kaesong where, on a steep hill, he built two matching burial mounds, one for himself, and the other for his wife. It is said that several astrologers were killed for displeasing Kongmin in his search for an auspicious site, including those who actually found the chosen location—slain in error by royal guards after Kongmin spent so long on the mountainside that they thought he had once again been taken to a location he did not like. The tombs of Kongmin and his wife were pillaged by the Japanese during their invasion of Korea in 1592 but have since been restored.

Although the Mongols dominated the kingdom of Koryo, when their power in China declined, it was a nervous time for the Koryo rulers. In 1382 the Chinese

Ming dynasty started and the remnants of the Mongols and the other tribes that had supported them fled north, with some making their way to Manchuria with Ming armies following them.

In equipping an army to hold off any moves across the Korean border, the Koryo rulers put a large armed force under the command of General Yi Song-gye. Rather than securing the border, Yi Song-gye moved on Kaesong and seized the kingdom for himself, ushering in the

Yi dynasty.