The city of Nagasaki is situated on the southeastern coast of the southern Japanese island of Kyushu. Nagasaki is port of entry for vessels coming from the south and the west.

Nagasaki was opened as an important trading port for the Portuguese in 1571 by Omura Sumitada, a major daimyo (feudal lord) of the area. Earlier, Francis Xavier, a Spanish Jesuit priest, had reached Nagasaki as the first Christian missionary to Japan. Initially, Oda Nobunaga, the military leader of Japan, tolerated Christianity.

However, his successor, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, banned Christianity in 1587 because he was afraid of the intense rivalry among the Dutch, Portuguese, Spanish, and English and feared the success of Christian missionaries in winning converts. Tokugawa Ieyasu, the successor of Hideyoshi, was initially friendly toward the Christians.

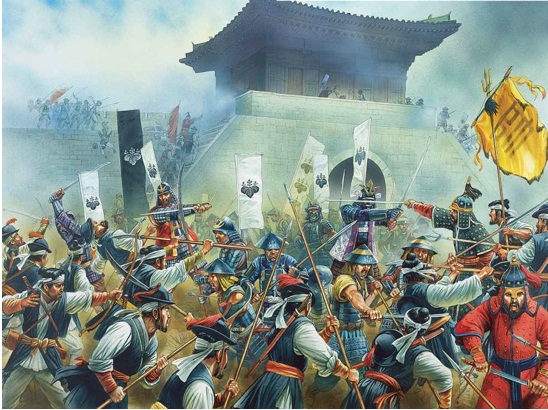

In 1614, however, he banned Christianity, as he too was afraid his authority could be challenged by the growing influence of the missionaries. One of the most infamous massacres took place in Shimabara, Nagasaki Prefecture, in 1638; 30,000 Japanese Christians were massacred.

The Dutch, whose Protestant faith was considered safer than the Catholicism of the Portuguese, were however allowed to continue trading in Japan. But Dutch activities were confined to the artificial island of Dejima in Nagasaki harbor under severe restrictions. As Japan’s only window to the Western world, Dejima became the center for Western or Dutch learning for two centuries.

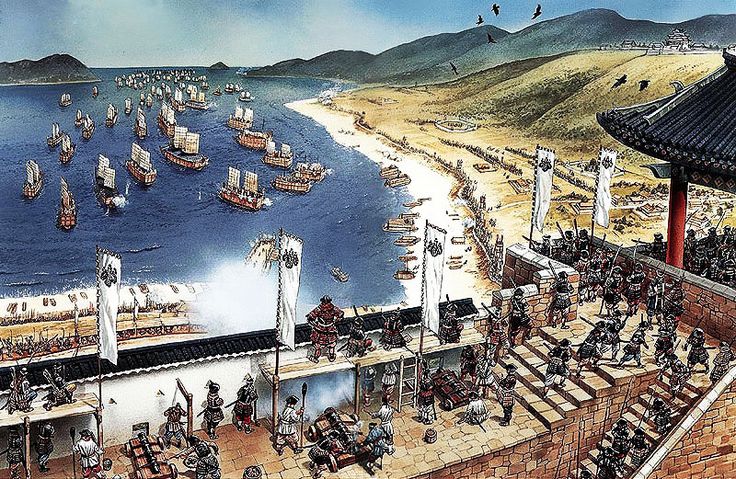

Chinese ships however were allowed to trade in Nagasaki. Ships came to Nagasaki harbor from all parts of China and imports from China to Nagasaki included silk, sugar, metals, medicine, and books. Japan’s main export to China was copper, primarily through Mitsui, Mitsubishi, and Sumitomo companies. During the 17th century, the number of Chinese settlers in Nagasaki rose to 10,000.

|

| Nagasaki |

Nagasaki was opened as an important trading port for the Portuguese in 1571 by Omura Sumitada, a major daimyo (feudal lord) of the area. Earlier, Francis Xavier, a Spanish Jesuit priest, had reached Nagasaki as the first Christian missionary to Japan. Initially, Oda Nobunaga, the military leader of Japan, tolerated Christianity.

However, his successor, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, banned Christianity in 1587 because he was afraid of the intense rivalry among the Dutch, Portuguese, Spanish, and English and feared the success of Christian missionaries in winning converts. Tokugawa Ieyasu, the successor of Hideyoshi, was initially friendly toward the Christians.

In 1614, however, he banned Christianity, as he too was afraid his authority could be challenged by the growing influence of the missionaries. One of the most infamous massacres took place in Shimabara, Nagasaki Prefecture, in 1638; 30,000 Japanese Christians were massacred.

The Dutch, whose Protestant faith was considered safer than the Catholicism of the Portuguese, were however allowed to continue trading in Japan. But Dutch activities were confined to the artificial island of Dejima in Nagasaki harbor under severe restrictions. As Japan’s only window to the Western world, Dejima became the center for Western or Dutch learning for two centuries.

Chinese ships however were allowed to trade in Nagasaki. Ships came to Nagasaki harbor from all parts of China and imports from China to Nagasaki included silk, sugar, metals, medicine, and books. Japan’s main export to China was copper, primarily through Mitsui, Mitsubishi, and Sumitomo companies. During the 17th century, the number of Chinese settlers in Nagasaki rose to 10,000.