|

| Natives of North America |

Perhaps no other group in human history has experienced as extreme a change in its circumstances as did the indigenous inhabitants of the Western Hemisphere between 1450 and 1750.

The so-called Columbian exchange, set off by

Christopher Columbus’s 1492 voyage from

Spain, completely altered the ecology, economy, and web of social relationships among the diverse peoples that Columbus (inaccurately) named “Indians.”

The people who populated North and South America between 40,000 and 15,000 years ago crossed what was then a land bridge between Siberia and modern Alaska and gradually settled the hemisphere.

When a worldwide Ice Age ended about 10,000 years ago, the land route between Asia and the Americas disappeared. By the time of Columbus’s first voyage, historians and anthropologists have estimated that the hemispheric population stood between 10 million and 75 million, most living in Central and South America.

The peoples of North America were diverse in almost every possible way except biologically. Experts argue about the extent of North America’s precontact population—the range is 1 million to 18 million—but most agree that populations began declining several hundred years before Europeans showed up.

By 1450, some large Indian communities in the Southwest, Pacific Northwest, and middle Mississippi Valley had vanished or dispersed, abandoning sophisticated buildings and artifacts. Factors that have been proposed to explain these declines include climate change, warfare, and disease.

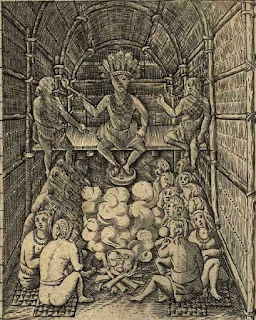

By 1450, there were dozens of tribal groups and alliances speaking diverse languages and following very different religious and social customs. There were some commonalities: Most Indians were animists, believing in the spiritual power of their natural surroundings.

They devised elaborate rituals to placate these spirits, especially those of animals they had killed. In many areas human burials were placed in elaborate and extensive earthen mounds. Most tribes respected shamans (healers) and believed that a Great Spirit oversaw the natural world.

Because tribes were likely to move often in search of better land or more abundant game—or to avoid other hostile tribes—property ownership in the European sense was all but unknown. Archaeologists have found abundant evidence of trade routes that spanned the continent, bringing tribes together in the process of tukar barang and exchange.

In most North American tribes, women were in charge of agricultural production, while men hunted for game. Maize (corn), first cultivated in Mexico, was by the time of contact a basic crop in much of North America.

Squash and beans were also staples of most tribes’ diets. While by no means environmentalists in any modern sense, most North American tribes were well adapted to their surroundings and were often helpful to inexperienced Europeans.

For example, natives taught French explorers how to build lightweight birchbark canoes to travel where their clunky wooden ships were useless. Others helped Europeans identify strange plants and animals, learning which were edible and which poisonous.

Most famously, Squanto, a Patuxet who had been kidnapped by an English slave trader in 1614, returned to America in time to teach the Pilgrims how to fish and grow corn, keeping them alive to hold a Thanksgiving in 1621.

Warfare was a constant among various Indian groups both before and after European contact. Early on, some tribal groups welcomed alliances with Europeans as a way to overpower their traditional rivals, in part by acquiring the foreigners’ goods and technologies, especially their superior weapons.

But as the trickle of Europeans became a flood, especially in British-claimed regions, some tribes forged alliances with traditional friends and even enemies to counter European threats to Indian survival.

For example, Algonquian chief Powhatan, head of a strong confederacy, at first welcomed Jamestown settlers, even allowing his daughter, Pocahontas, to marry Englishman John Rolfe.

But in 1622, Powhatan’s brother Opechancanough, now leader of the

Powhatan Confederacy, launched a surprise attack on settlers, killing more than three hundred of them and capturing women and children. Ultimately, the Virginians rallied, using trickery and even poison to reclaim their holdings.

In this early war, as in later conflicts, tribes were responding to growing white populations. Whites were no longer perceived simply as traders who would soon move on; they had become settlers using—and claiming as their own—traditional tribal lands.

Disease did even more damage than European land grabs and weapons of war. Because Indians were genetically very similar, and because they had been isolated in the New World for many centuries, they were at the mercy of pathogens carried by the invaders.

The worst of these was smallpox, with measles and influenza also sowing death. These diseases killed Europeans, too, but ravaged the Indian population. Long before germs were known to cause disease, Europeans praised God for smiting Indian enemies, thus making it easier to colonize America.

Some Europeans “assisted” this process by purposely distributing to Indians smallpox-infected blankets and other tainted goods. Smallpox epidemics could and did change the course of battles and negotiations between natives and Europeans.

Southwest Descendants of the Anasazi, whose complex civilization came to a puzzling end in about 1300 c.e., the Pueblo Indians, including Hopi and Zuni, for centuries had lived in settled agricultural communities in today’s southwestern United States.

The Spanish, who had already made a fortune exploiting Central and South America, in the 17th century also began aggressively exploring the southern reaches of North America, with terrible consequences for the native population. In 1598,

Juan de Oñate marched four hundred soldiers, priests, and colonists into New Mexico, killing almost half the residents of the cliff city of Acoma and forcing most of the rest into slavery.

In 1680, Popé, a Pueblo religious leader who had been punished for rejecting Franciscan priests’ attempts to convert him, led the

Pueblo Revolt, the most successful native retaliation in this masa of European occupation.

Indian ranks had thinned through disease and compelled labor, but they still outnumbered the Spanish colony of about three thousand. The Pueblo peoples spoke several different languages, yet they managed to unite, with the help of traditionally hostile Apache, to expel the Spaniards and destroy symbols of Catholicism.

Although internal native strife, including raids by Apache and Navajo enemies, soon resumed, and the Spanish retook New Mexico in 1692, the Pueblo were treated with greater respect, becoming one of the few tribal groupings in North America to mostly retain ancestral homelands.

Southeast and Florida In 1513, Hernán Ponce de León invaded Florida in search of slaves, wealth, and promises of eternal youth but was repulsed by local Calusa Indians. More sustained and far-ranging efforts led by Hernando De Soto and others in the 1540s explored the Gulf coast and penetrated as far as the Great Plains. Not until 1565 did King

Philip II authorize what was essentially a Florida military base to deter British, French, and Dutch piracy of Spanish gold.

In the process, the Spanish massacred a tiny colony of refugee French Huguenots and built a fort at St. Augustine, the oldest U.S. site continuously peopled by Europeans. Efforts to convert the local Guale tribe sparked an uprising in 1597. The tiny Spanish colony put down the uprising in 1602 but never attracted more than a few thousand settlers.

In other sections of the Southeast, a confederacy among four tribes—the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, and Creek—preceded the European invasion. They would be tested by European incursions that forced these tribes to relocate, sometimes competing among themselves for territory.

By 1745, the Cherokee were allied with the British in their effort to contain France and Spain, focusing on lands between Florida and the recently established colony of Georgia. In this period, Creek began migrating to Florida under pressure from both Europeans and members of their own tribe. In the 19th century, they would call themselves Seminole.

British and French American Alliances The five (later six) tribes that became the Iroquois Confederacy (Haudenosaunee) centered in what became New York State, had also, prior to European contact, initiated a Great League of Peace in response to destructive warfare among tribes.

These “people of the longhouse” included the Mohawk, Seneca, Onondaga, Cayuga, and Oneida tribes, joined in the early 1700s by Carolina’s Tuscarora. The Iroquois were not nomadic but lived in large villages. Their longhouses were wood and bark structures that might be 400 feet long and accommodated many family groups.

Skilled negotiators, the tribes individually and confederacy as a whole for a time held their own against Dutch, British, and French claims and demands. Some among the Iroquois hoped to remain neutral, but they soon were edging toward the British.

By the 1670s, the Iroquois and British had pledged mutual friendship. After a sneak attack by French forces in 1687, the Five Nations retaliated by attacking New France settlements on behalf of British objectives in what was known in North America as King William’s War.

They fought both the French and France’s Indian allies, including the Huron and Abenaki and Algonquian people of the Great Lakes region. Both groups of Indians inflicted and suffered terrible casualties; by 1701, the Iroquois were promising their people to remain neutral in future European conflicts.

By 1750, eastern and Great Lakes Indians of many tribes, displaced by white settlement, were seeking new lands in the Ohio Valley, on the frontier between British and French territorial claims and control.

The Iroquois, as well as Shawnee, Delaware, Cherokee, and Chickasaw, were all trying to use this no-man’s-land to enhance trade and perhaps prevent both the British and French from expanding even farther into the continent.

In 1749, Virginia awarded some of its favored citizens development rights to almost 8,000 square miles of the Ohio Valley. The ensuing French and Indian wars would set off a series of events that ultimately made hundreds of Native tribes—survivors of 258 years of warfare, land loss, and disease—strangers in their own land.