|

| Alawi Dynasty in Morocco |

The dynasty’s name was derived from the name of its ancestor, Mawlay Ali al-Sharif of Marrakesh. Mawlay Rashid (667–722), the first Alawite ruler of Morocco, is considered to be the founding father of the dynasty.

The name Alawi is also used in Morocco in a more general sense to identify all descendents of Ali, who was the cousin and son-in-law of the prophet Muhammad. At the time the Alawi surfaced in Morocco, sultan kings with absolute power had ruled Morocco for almost four centuries.

In the 16th century, Morocco’s sultan kings had been forced to make decisions about foreign trade. While the rulers wanted the gunpowder and arms that trading with Europe could bring, they were hesitant to trade with the continent that Moroccans knew as the “land of infidels.”

Weapons were particularly important for Morocco at that time, because the country was facing Iberian expansion along the Atlantic and Mediterranean coasts. Members of the Alawi dynasty were also cognizant of the possibility of their becoming a target of European colonialism.

The rulers not only wanted to protect Morocco from foreign invaders, but they were also determined to maintain the purity of their Muslim society. In the past, they had accomplished this goal by banning foreign travel and restricting contact with all foreigners. Yet, the likelihood of continuing such practices was diminishing since foreign trade had become an essential economic activity.

In 1666, Mawlay Rashid of the Alawi dynasty seized power after the death of Ahmad al-Mansur of the Sa’did dynasty. Rashid came to power by outmaneuvering Ahmad al-Mansur’s three sons. Rashid also killed his own brother, Mawlay Mohammad, who challenged him for the right to rule Morocco.

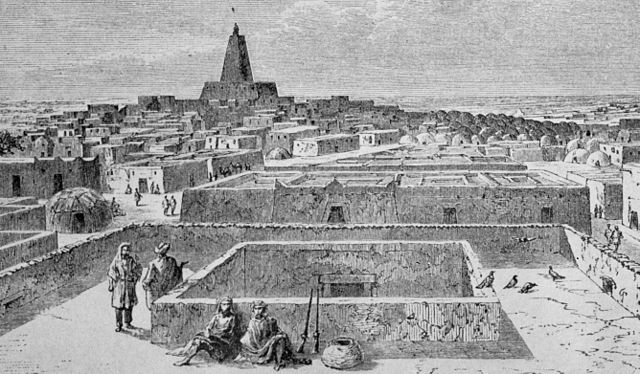

Once in power, Rashid appointed the ulema (a group of learned religious men) and noted scholars as his advisers, and he celebrated his victory by holding elaborate ceremonies that combined elements of Moroccan politics, religion, and culture. These rituals were designed to introduce the Moroccans to their new leader and to demonstrate the right of the Alawi to rule Morocco because of its strong connection with the past.

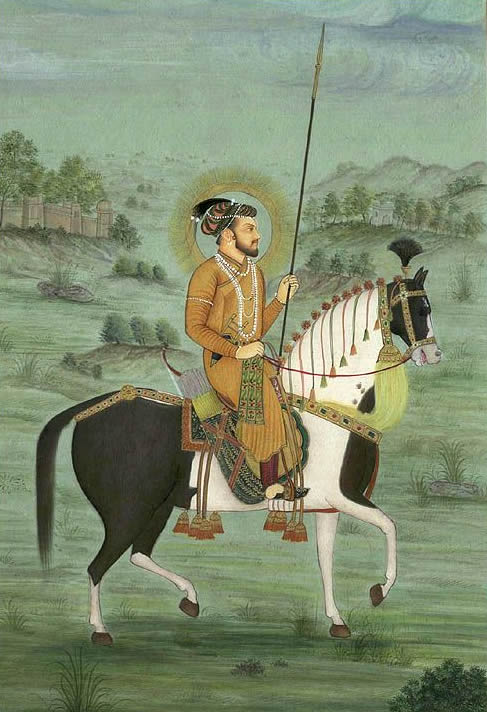

In 1672, Mawlay Isma’il succeeded his brother as the ruler of Morocco after Rashid was killed in a riding accident. Isma’il became known as the greatest sovereign of the early Alawi period. He established a form of government that survived until the 20th century.

Isma’il also reached out to the French, with whom he formed an alliance against the Spanish. The partnership resulted in a steady supply of weaponry into Morocco and in a number of construction projects for new palaces, roads, and forts.

To finance these projects, Isma’il levied heavy taxes and demanded ransoms for imprisioned Europeans. Rashid had great respect for scholarship, and he built Madrasa Cherratin in Fez and an additional college in Marrakesh. Rashid also reformed the monetary system and ensured that wells were dug in the eastern deserts.

In the 17th century, Alawi nationalists launched a jihad (holy war) designed to strip local Christians of all land located on the Atlantic and Mediterranean coasts of Morocco. The Alawi dynasty continued to rule Morocco from the mid-17th century until 1912, when the country became a protectorate, with Spain controlling northern Morocco and France ruling the southern part of the country.

In 1956, Morocco reestablished its independence, and the Alawi monarchy again rose to power under the rule of King Mohammed V. Since that time, the Alawi dynasty has continued to rule Morocco.

In the 21st century, Moroccan members of the Alawi dynasty continue to practice close adherence to Sunni Islam. Moroccan scholars have scientifically documented the Alawi claim to be directly descended from the prophet Muhammad. As a result, the Alawi dynasty continues to hold wide legitimacy in contemporary Morocco.

The Alawi are credited with bringing economic prosperity to the country by growing the economy, establishing foreign trade links, and improving the overall standard of living. A Syrian branch of the Alawi dynasty, which practices the Shi’i school of thought, follows the teachings of Muhammad ibn Nusayr. More liberal than the Moroccan Alawi, the Syrians celebrate both Muslim and Christian festivals.