|

| Iranian Revolution |

The Iranian revolution of 1979 overthrew the Pahlavi dynasty and established an Islamic republic. In 1953 when it appeared that the monarchy was about to be overthrown, the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) helped to orchestrate a countercoup that kept Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi in power.

Iran, under the shah, was closely allied with the United States and in the cold war Iran was a staunchly pro-Western buffer on the southern flank of the

Soviet Union. Iran was used as a base for United States military and intelligence gathering aimed at the Soviet Union. The United States also supplied considerable assistance to the shah.

In 1961 the shah announced an ambitious plan of development known as the

White Revolution. The sixpoint plan included improvements in women’s rights, healthcare, and education, as well as privatization of state-owned factories and land reform.

The proposed nationalization of land owned by the clergy and landed elites led to major demonstrations against the government. The shah repressed all political opposition, and his secret police, SAVAK, imprisoned and often tortured opponents of the regime, especially members of the Iranian communist Tudeh Party.

Conservative businessmen in the Tehran bazaar, traditionally a major force in Iranian politics, and the clergy were also offended by the lifestyles of the elite, who emulated Western dress, consumed alcohol (forbidden to Muslims), and practiced open relations between the sexes.

Even the Iranian middle class was dismayed by the extravagant expenses of the 1967 formal coronation of the shah and his wife and the 1971 celebration of the 2,500th anniversary of the Peacock Throne at

Persepolis. In the 1970s Iran became a regional power when the shah used increased revenues from petroleum to buy sophisticated armaments, mostly from the United States.

A number of Iranian intellectuals laid the groundwork for the revolution in books and treatises critical of the Pahlavi regime. Samad Behrangi (1939–68) wrote popular folktales that were in fact veiled critiques of the shah’s regime.

He also wrote against what he called “west struckedness,” or intoxication with all things Western. Jalal Al-e Ahmad (1923–69), a writer from a clerical family, described those Iranians who copied the West as diseased.

Ali Shari’ati (1933–77) was the most influential Iranian social critic. A sociologist, Shari’ati was educated at the Sorbonne. He was familiar with Marxist thought but fused it with Islam, arguing that independent reasoning should be applied to interpreting the Qu’ran to create a new society.

A prolific writer, Shari’ati was a major influence on a new generation of Iranian students. In an attempt to halt his writing and political activity, the government arrested Shari’ati, who was tortured, released, and then placed under house arrest. His books were banned, and he died in exile in London.

The clergy also opposed the shah’s efforts to undermine their authority and stop government subsidies for religious schools. Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, a leading cleric in Qom, a conservative center for the training of Shi’i mullahs, was particularly outspoken in his hostility to the shah.

An expert on Islamic law, Khomeini spoke against the acquisition of U.S. military equipment and favored treatment in Iran, and he was arrested several times in the 1960s. In 1964 he was sent into exile to Turkey, and he then took up residence in the Shi’i holy city of Najaf in Iraq, where his activities were closely monitored by the Iraqi government.

In 1978 the shah convinced

Saddam Hussein to oust Khomeini, who then moved to France, where he had access to the media, enjoyed freedom of movement, and attracted a loyal following among dissident Iranians.

The shah’s regime was accused of increased corruption and nepotism while the gap between the wealthy who lived lavish lifestyles and the poor in the countryside and urban slums widened.

The revolt against the regime began in January 1978, with riots in Qom protesting an anti-Khomeini article published in a newspaper. Police forces moved in to crush the riot and killed 100 protesters.

To commemorate their deaths as martyrs, protests took place in Tabriz and Yazd in March; these demonstrations led to more deaths when the police moved in to stop them. This initiated a 40-day cycle of riots and repression, with inevitable deaths.

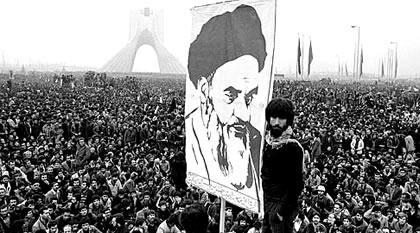

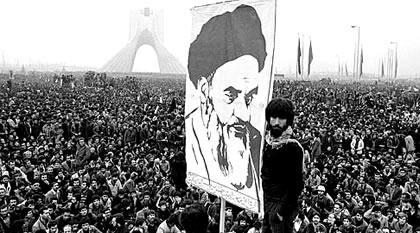

In May riots broke out in 34 towns. The demonstrators were encouraged by speeches by Khomeini on cassette tapes that were smuggled into the country. Khomeini emerged as the symbol of opposition to the shah’s regime.

In August a fire set by the shah’s appointees at a cinema in Abadan killed an estimated 400 students who had gathered to protest the regime. This was followed by “Black Friday” in September, when demonstrators were massacred in Tehran.

By the fall a new pattern of strikes by students, teachers, and their supporters emerged. In December, government workers and employees in the petroleum industry as well as the army joined the protests. Women were also active participants in these demonstrations. Most of those who lost their lives were young Iranians, often from the Left.

The clergy remained largely in the background but would emerge as the major political force after the fall of the monarchy. The United States failed to find a substitute for the shah, who seemed convinced that Washington would step in to save his regime.

In the face of mounting violence and lack of support even within the military, the shah, ill with cancer, fled the country in January 1979. He left a caretaker government under Shapour Baktiar, who had no base of support.

Khomeini returned amid massive demonstrations of support in February. Following Khomeini’s triumphal return, Baktiar fled Iran and was replaced by Mehdi Bazargan. The Iranian Islamic Republic was established on April 1, 1979.

The shah was allowed into the United States for medical treatment in the fall of 1979; this inflamed Iranians, who had demanded his return for trial. The shah, who had difficulty finding a country to grant him asylum, died in Egypt in 1980.

In Tehran students, many of them members of newly formed, self-appointed committees (kometehs), stormed and took the U.S. embassy and held U.S. hostages for over a year. Khomeini used the resulting crisis and chaos to help cement the clergy’s control over the new government. Right-wing Hojatieh groups supporting militant Islam also emerged; they were supported by some ayatollahs and bazaaris.

The 1979 constitution provided for a Majlis (parliament), a president elected by direct representation, and a velayat e faqif, a spiritual leader, to act as the simpulan authority in the nation. Khomeini was named the first faqif.

The Council of Guardians acted as a supreme court to review all legislation of the Majlis. The council frequently rejected parliamentary legislation such as trade nationalization and land reform as un-Islamic.

Abolhassan Bani-Sadr was elected the first president by a wide margin in 1980, but he was removed from office by Khomeini in the summer of 1981. Sadr then went into exile to France. Khomeini repressed political opponents and purged members of the old regime as well as the leftist opposition, such as the Fedayin alKhalq.

The Iranian Revolution had a huge impact on the Islamic world, and many young Muslims, discouraged by the corruption and ineffectiveness of the governments in their own countries, looked to Iran as a possible model for

future changes.

Khomeini’s open support for regime change in neighboring Arab nations aroused the fears of

Saudi Arabia and other states and led to the

Iran-Iraq War. However, in spite of internal contradictions, domestic opposition, and condemnation by many international forces, the Islamic regime proved to be remarkably flexible and long lasting.