|

| Akan States of West Africa |

The Akan people of

West Africa are descandants of the residents of the early Akan states and continue to live in the area east of the Mende people that makes up present-day Ghana and the Ivory Coast. It is believed that the Akan people have been present in West Africa since the first century.

However, it was not until the 15th century that the world outside Africa became aware of the Akan states. Most of the early

information on the Akan came from the Portuguese who developed the West African gold trade.

When the Portuguese first appeared in West Africa, the area controlled by the Akan states stretched from the equatorial forest southward to the Ofin and Pra Rivers. This area roughly compares to what later became the states of

Ashanti and Adansi.

While locals called the early Akan settlements Akyerekyere, Europeans identified the people as belonging to two separate groups, the Akany and Twifu (or Twifo). While a number of scholars suggest that members of Akan states were of Dyula ancestry, others disagree. It is true that a number of Dyula settlements existed in Akan states, but the most prevalent view is that Akan states grew in strength to rival Dyula rather than evolving from it.

Further arguments that support the belief that the Akan states were separate from Dyula center on cultural differences. Two customs that were distinctly Akan in nature and that had no counterpart in Dyulan culture were the annual yam festivals and the tradition of matrilineal inheritance.

Subsequent studies of the Akan people have led scholars to believe that the southern branch of the Akan, the Fante, traveled in earlier times from the Volta Gap to the coastlands of Accura, where they intermarried with existing inhabitants.

As the area expanded, several powerful Akan states emerged. The oldest of these is thought to be Bono, which was also called Brong. Asante, which later came to be known as Ashanti, proved to be the most powerful Akan state. Others included Akwamu, Denkyira, Akyem, and Fante.

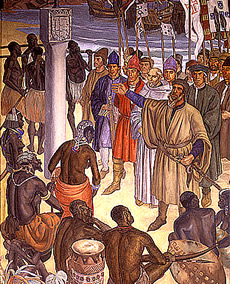

Europe and the Akan States When the

Portuguese established their presence in West Africa in 1471, they discovered that the Akan people were not living in towns, as was typical in Africa during this period. Instead, the Akan were occupying small kingdoms ruled by kings and queens in the savanna north of the existing gold belt.

Within each kingdom, families that were descended from seven or eight particular clans, identified by matrilineal lineage, lived in villages where they were ruled by their own chieftains. In addition to the chieftains, each family and clan had its own leader. All of the families, clans, and villages worshipped gods that they had individually deified. The various lineages also had their own symbols, which were used to identify matrilineal ancestry.

Once it became clear that the gold trade would develop into a significant economic undertaking, the Akan states realized that it was in their best interest to control the route to and from the Gold Coast.

As a result, the Akan states took on a prominent role in developing West Africa. Early on, the Akan depended on three significant areas to establish their presence in the gold trade. The first of these was Bona, which was located close to the Lobi gold mine.

The others were Banda, which controlled passage to the main gold trading route through the Volta Gap, and Bono, where Bono-Mansa, the capital of the early Akan states, was located. Over the following decades, the gold trade with Portugal exploded, reaching its peak in 1560 with West African gold providing one-fourth of all revenue for Portugal.

From the earliest days, the Akan had been heavily involved in agriculture, developing a farming belt along the outer environs of the equatorial forest where they grew yams and oil-producing palms.

Other agricultural activities included the production of plantain, bananas, and rice, as well as collecting kola nuts, raising livestock, hunting, fishing, and making salt. The density of the soil in and around the forest limited the type of produce that could be grown, and increasing populations soon exhausted the soil.

As a result, the Akan people entered the equatorial forests, where they cleared enough land to support the needs of the people. In the 17th century, agricultural production and the growth of the trade along the

Gold Coast led to permanent settlements in the equatorial forest.

Rates of urbanization and increasing sophistication among the Akan states subsequently led to the emergence of more complex political and social structures. Strong leadership among the people of the Akan states allowed them to retain their own cultures in the midst of the expanding European presence, while winning the respect of the Europeans in the process.

Slavery in The Akan States In the past, attempts by some Akan leaders to dominate the entire region had resulted in tribal wars. As a result, victorious tribes had begun selling members of conquered tribes at local European

slave markets.

The more vulnerable tribes, such as the Ewe who lived in the lower Volta area, were continually subjected to being enslaved. Additionally, certain Africans were born into lineage slavery and were forced from their earliest years to serve the dominant African groups. The Akan states also bought slaves from the Portuguese.

Most of these came from Benin, where the government regularly sold off its captives. After 1516, when the government of Benin reduced its military activity, most of the slaves that the Akan states purchased from Portugal came from the Niger Delta and the Igbo region.

The Akan states retained some slaves for local use, while others were placed on slave ships bound for markets along the

Atlantic slave-trading route. Domestically, the Akan states used slaves in royal households and in transporting goods to market. Additionally, large numbers of slaves were put to work in construction, in mines, and on farms.

A smaller number of slaves were employed as artisans in various crafts. The Akan states also designated some slaves to be trained to use flintlock muskets as part of citizen armies employed in the Akan quest to crush neighboring states and expand the existing Akan empire.

Along with slaves, the Akan states also commandeered the services of immigrants and migrants to be employed in various tasks. In general, both slaves and forced labor were allowed limited freedom because their numbers prevented total control over the population.

Rivalry Among Akan States As individual states became more powerful, competition arose among the Akan states, with Denkyira and Akwamu emerging as the most powerful. By the middle of the 17th century, Denkyira had won the right to control most of the western gold-bearing area and had begun forging an empire leading northward to the established European trading routes that led to Banda and Bono.

During the 1670s, Denkyira seized control of the entire area around the western Gold Coast and beyond. On the eastern coast, Akwamu had begun to do the same. From 1677 to 1781, Akwamu worked on its campaign to win control of Accara, which had been under Denkyira control since 1629. Ultimately, Akwamu annexed Accara, in addition to the surrounding areas of the eastern territory.

This expansion provided them with direct control of the trading forts operated by the English, Dutch, and Danish along the eastern Gold Coast. Thus, by 1702, Akwamu had also gained control of the east coast slave-exporting businesses. Despite their enormous strength, greed ultimately destroyed both Denkyira and Akwamu.

Asante, which had originally been a dependency of Denkyira’s, emerged as a major contender in the ongoing power struggle of the late 17th and early 18th centuries, giving birth to the powerful Ashanti state. Ashanti was formed from the various Akan states that had gathered together in the north-central section of the equatorial forest.

The combined strength of these states enabled them to dominate the trading route from western and central Sudan. Within the state of Ashanti, the various kings agreed to accept the supremacy of one king to be based in the capital city of Kumasi. The first Ashanti king was Osei Tutu (c. 1680–1717).

In 1698, Osei Tutu declared war on Denkyira, using arms from Akwamu. In 1701, Ashanti finally succeeded in overwhelming Denkyira, thereby gaining essential territory for its southward expansion.

Three decades later, Akyem, an important Ashanti ally, defeated Akwamu. After the downfall of Denkyira and Akwamu, Ashanti became the most powerful influence in the area now known as Ghana, continuing to rule until the end of the 19th century when the British conquered the area.

Ashanti Development and Expansion Over the course of the 18th century, Ashanti strengthened its hold on the central forest region and began reaching outward to expand its territory. Each captive area was forced to pay tribute to Ashanti. Areas such as Dagoomba in the northeastern area of the equatorial forest paid their tribute in slaves, which had in turn been taken captive from more remote areas of Africa.

Ashanti then traded those slaves for firearms, smelted iron, and copper. Between the 15th and 19th centuries, some 4 million slaves had been taken for this purpose from south of the equator in an area that extended from Cameroon to Kunene.

Until the pope banned the sale and trade of European firearms to Ashanti out of fear that radical Muslims would lay hold of the guns and use them against Christian traders, the Portuguese regularly traded weapons to Ashanti in exchange for slaves.

By 1820, the Ashanti Empire controlled some 250,000 square kilometers that had been organized into three distinct regions. The first was composed of the six metropolitan chiefdoms that had furnished the military power for

King Osei Tutu.

The bulk of the people of Akan descent lived in the second region. The third was composed of dependencies, such as Gonja and Dagomba, which were required to pay tribute of 1,000 slaves each year.

Since the strength of the Ashanti state was always dependent on the force of its military rather than on a sense of nationalism, it became impossible to maintain a hold on those tributary states that made up two-thirds of the Ashanti Empire. This weakness made Ashanti more vulnerable when the British declared war on the state in the 19th century.

Today, the remaining Akan people belong to either eastern or western Akan groups. The five groups of eastern Akan, which all speak Twi, include Asanta, Auapem, Akyem, Denkyria, and Gomua. Sehwi-speaking Western Akan is made up of Anya, Ahanta, Baule, Sanwi (Afema), Nzima, and Aowin.

Despite the fact that each subgroup has its own dialect, groups are able to communicate with one another. While the Akan people continue to practice the tradition of matrilineal descent, some changes have been instituted to make inheritance laws more equitable.