|

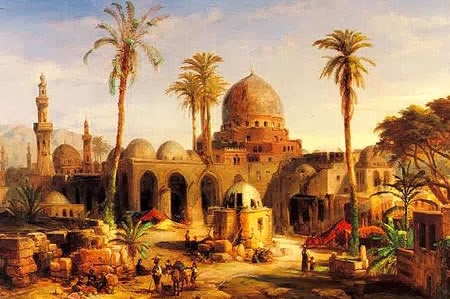

| Art and Architecture in the Golden Age of Muslim World |

Islamic art and architecture is that of the Muslim peoples, who emerged in the early seventh century from the Arabian Peninsula. The Muslim empire reached its peak during the golden age of Islam from the eighth to the 13th century.

Literary and archaeological evidence reveals that the early architecture of the Muslim communities in Medina and Mecca, presented through the prophet Muhammad’s mosque and residence in Medina and through other smaller mosques, continued the indigenous building style based on a rectangular structure with an open internal courtyard and a covered area. Older structures such as the Ka’aba in Mecca continued the ancient Arab architectural style found among the Nabataeans in Petra, Palmyra, South Arabia, and Hatra in Mesopotamia.

In pre-Islamic times, the inhabitants of the Arabian Peninsula and its surrounding regions lived in scattered minority communities of Jewish, Christian, and Zoroastrian peoples among a majority of pagans or polytheists.

To these people, great legendary architectural palaces, castles, temples, and churches were still-vivid memories signifying power and prestige. They were recorded in poetry and other literary forms and associated with famous cities such as Petra, Palmyra, Hatra, Hira, Madain Salih, Kinda, Najran, Marib, and Sana.

Pre-Islamic records and literary evidence attest to the existence of visual art forms, especially sculpture and painting, which were employed primarily to disseminate copies of icons and sculptural depictions of the many deities and idols worshipped in the region.

For example monumental statues of major deities like Hubal, Allat, Al-Uzza, and others were still standing in public locations and temples on the eve of the advent of Islam prior to 630. Small-scale statues and figurines were abundantly available among the pre-Islamic population, and makers of images were active in such cities as Mecca and Taif.

Wall paintings from the early Islamic secular buildings in Syria, Jordan, and Iraq reveal important examples of a blending of Mesopotamian, Sassanian, Hellenistic, and indigenous Arab styles. Architectural planning of early Muslim mosques in Egypt and North Africa reveals borrowing from ancient Egyptian architecture.

Early Islamic Art and Architecture  |

| Great Mosque of Damascus |

The prophet Muhammad died in 632 and within a few years the newly emerged Islamic state expanded quickly and swiftly claimed the realms of both the Sassanian and Byzantine Empires. In less than 100 years the new politicoreligious model reached the steppes of Central Asia and the Pyrenees in Europe.

As the Muslim community expanded, the need for a central place of worship emerged and was realized by the development of the mosque—a French distortion of the word masjid or “place of prostration.” Islam, a nonclerical, nonliturgical faith, does not employ ritualistic surroundings and the first mosque was actually the open courtyard of the house of the prophet Muhammad in Medina. It functioned as a meeting place and community center.

Later this tradition expanded to the establishment of a central mosque called al-Masjid al-Jami'—“the great mosque”—in every major city. With it developed the characteristics of the mosque and its components: an open courtyard (sahn); a roofed area for prayer (musallah) with a dome (qubba); a niche in the wall of the prayer area (mihrab) to indicate the direction of prayer (qiblat) toward the Ka’aba in Mecca; an elevated platform (mimbar), from which the congregational leader delivered the sermon; a tower (minaret), from which the call to prayer (adzhan) was issued; and an ablution place for performing the ritual washing before each prayer (wudhu).

This basic arrangement of functional space found in early mosques in Basra, Kufa, and Wasit in Iraq, and later in the

Great Mosque of Damascus and the Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem, and elsewhere, became the prototype of traditional Islamic mosque architecture.

The rapidly growing state demanded a new Islamic architectural style that developed gradually, acquired new forms, and incorporated diverse methods of visual expression. During the golden age of Islamic civilization a blend of architectural designs and motifs from South and North Arabian, Byzantine, Hellenistic, Indian, Chinese, and other origins was employed in a new building kegiatan throughout the Islamic world.

Whatever the variety of its components, the jawaban result always presented a unique Arab Islamic style, especially in the early period, where the architecture and art were unified by strong Arab characteristics that can be detected in the art of the Umayyads in Syria, the Andalus in Spain, the Abbasids in Iraq, and the Fatimids in Egypt.

The Arabic language, derived from the Semitic Aramaic language, played a decisive role in the formation of Islamic culture and art. Arabic was the official and original language of the Qur’an, the holy book of Islam. Arabic was a powerful cultural and literary vehicle with which to disseminate Arab culture throughout the new and diverse Muslim communities in the recently expanded regions of Central Asia, Anatolia, the Mediterranean coasts, Sicily, and Spain.

Verses of the Qur’an were inscribed in elegant Kufic and Thulth calligraphic styles on the interior and exterior of major mosques in Jerusalem, Damascus, Basra, Fustat, Tunisia, Sicily, and Spain in a variety of techniques such as stucco, wood carving, and ceramic tiles. The mosque thus became a unifying architectural form and symbol of the monotheistic concept of Islam.

Islam adopted an aniconic style in art that does not promote figurative representation. In the Qur’an, the sunna (manners, ethics, behavior, and social practice of the prophet Muhammad), and hadith (collection of sayings of Muhammad pertaining to a variety of topics, and everyday life situations), depiction of living forms is discouraged and according to certain interpretations is banned altogether, especially in religious environments such as mosques.

Sunni orthodox interpretation of figurative representation characterized it as an act of defying the power of God, who alone was ascribed the ability of creation. Furthermore the depiction of human beings was also thought to be reminiscent of and an encouragement of pre-Islamic idol worship.

These sanctions prompted Muslim artists to create a new form of expression based on the use of Arabic calligraphy—literal meaning and visual composition—and decorative ornamentations. The corroboration of these two powerful visual vocabularies with the already developed conventional Islamic components characterized Islamic art distinctly and continuously.

Umayyads: 661–750 c.e. Borrowing, blending, and modifying motifs, forms, and techniques from Byzantine and Sassanian sources and incorporating them into the indigenous Arabic style characterize the art and architecture of this formative period. This approach was presented through the architectural planning and iconographic design in major buildings, both religious and secular.

|

| Interior of Umayyad mosque |

In the eastern Mediterranean region a new blend of styles and motifs was incorporated in the early Umayyad buildings. Mosaic decoration, a preferred Byzantine medium, is evident in the case of the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem, completed in 692; the Great Mosque of Damascus, completed in 715; and the desert palaces in the Syrian regions.

Presentation of power, triumph of the new religion, and the emphasis on Islamic theology in early Islamic art were realized through the use of monumental architectural forms, calligraphy, and the ornamental aniconic patterns as in the case of the Dome of the Rock, or the figurative representations in painting and sculpture at the desert palaces Qusayr Amra, Khirbat al-Mafjar, and Mshatta in the Syrian region, and during the early Abbasid period in palaces in Samarra and Baghdad in Iraq.

Abbasids: 750–1258 c.e. Beginning around the 10th century the synthesis of Islam and Arab culture was modified by the emergence of decentralized, mostly non-Arab political powers such as the Samanids in Iran and the Ghaznavids in Afghanistan, the Seljuk dynasty in Anatolia, the Fatimid dynasty in Egypt and Tunisia, and the Almoravid Empire (al-Murabitun) and Almohads (al-Muwahhidun) in the western areas of Islamic lands.

These dynasties and mini independent states contributed to the spread of Islam and consolidated their political power in the Andalus in Spain and established bases in the heart of India with the Delhi Sultanate in 1206. Traders and merchants carried Islam as a religion and culture deep into Africa and Central Asia, and across the sea routes to Indonesia.

These new political powers with their cultural trends added new riches to the diverse collection of Islamic science, literature, art, and architecture. Baghdad, the capital of the Abbasid dynasty, became the center of knowledge and scientific development.

The Islamic Renaissance The Islamic renaissance, which witnessed tremendous advances in every field, prompted architects, visual artists, calligraphers, and artisans of all sorts to collaborate in the production of a vast body of monuments, masterpieces, and manuscripts.

A great number of these manuscripts were embellished and illustrated with fine visual presentations, such as the 13th century Maqamat al-Hariri illustrated by Mahmoud bin Yehya al-Wasiti, whose style set a standard for what is conventionally known as the Baghdad school of al-Wasiti. The diverse cultural input of new ethnic groups from Iran, Anatolia, Central Asia, India, and the Mediterranean region enriched the Islamic art repertoire.

|

| interior of the great mosque of cordoba |

Figurative illustrations gradually populated manuscripts, especially those of a literary or scientific nature. Figurative representation was used during the Abbasid, Fatimid, Seljuk, Mamluk, and later periods as well. It is important to note that depictions of human figures, although employed by both Shi’i and Sunni artists and patrons, were most common with Shi’i and Sufiart.

In architecture, a blend of new elements from the recently acquired territories was incorporated in the design of mosques, hospitals (maristan), schools (madrasat), Sufi foundations (khanaqah), tombs, shrines, palaces, and gardens. This incorporation furthered and enhanced the defi nition of a distinct Islamic style. Muslim architects developed and employed the pointed arch as early as 776 at the al-Ukhaydhir palace in Iraq and the al-Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem in 780.

The pointed arch concentrates the thrust of the vault on a narrow vertical line, reducing the lateral thrust on foundation and allowing for higher walls. The double tier arch and the horseshoe arch were developed and used in the Great Mosque of Damascus in 715 and transmitted later to the Andalus in Spain and employed in the

Great Mosque of Córdoba. The square minaret appeared for the first time at the Great Mosque of Damascus and was transmitted later to North Africa and Spain. The pointed arch, horseshoe arch, and the square minaret impacted European architecture and were adopted in Romanesque churches and monasteries and especially in the Gothic cathedral and its towers. Much of the Islamic golden age achievement passed on to Europe through Sicily, Spain, Jerusalem, and other important centers in the Islamic world.

Muqarnas is probably the most distinct and magnificent architectural decorative element developed by Muslim architects around the 10th century, simultaneously in the eastern Islamic world and North Africa. Muqarnas is a three-dimensional architectural decoration composed of nichelike elements arranged in multiple layers. Soon after its appearance, muqarnas became an essential architectural ingredient in major buildings of the Islamic world in Iran, India, Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria, Egypt, Sicily, North Africa, and Spain.

Muqarnas structures, augmented with the elegant Arabic calligraphy, floral design, and geometric patterns typically called arabesque, produced a dazzling visual composition that characterized the beauty of such places as the interior of the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem or the Masjid al-Jami’ in Isfahan, among other examples.

This composition, accentuated by bands of the Kufic and Thulth styles of Arabic calligraphy, added spiritual and poetic dimensions to the adorned buildings and objects. Qur’anic texts usually cover the exterior and interior of religious buildings with verses and chapters at various locations in the building.

Poetry, proverbs, and celebrated sayings may cover secular buildings and nonreligious objects such as dishes, plates, and jewelry boxes. The continuous patterns and repetition of ornaments covering walls and ceilings, running along naves, arcades, and archways, echo a rhythmic tone that originates from one pattern and multiplies in endless, complex, repeated, and variant patterns.

It defines the unity in multiplicity of Islamic decorative style. This attractive visual system was so impressive that some early Renaissance artists could not resist copying and imitating bands of Kufic inscriptions to decorate the clothing of the figure of the Virgin Mary and other biblical figures and angels in paintings of the period.

The golden age of Islam witnessed the emergence of elegant visual art and magnificent architectural achievements that had a major influence on succeeding periods, with its characteristics echoing throughout the Safavid, Mogul, and Ottoman periods.