|

| Uganda |

The area known today as Uganda was part of the charter of the British East Africa Company in 1888, and was ruled as a protectorate in 1894. As more territory was added to the British claims, the boundaries of what now form Uganda took shape in 1914. It was ruled as a British protectorate until given autonomy in 1962.

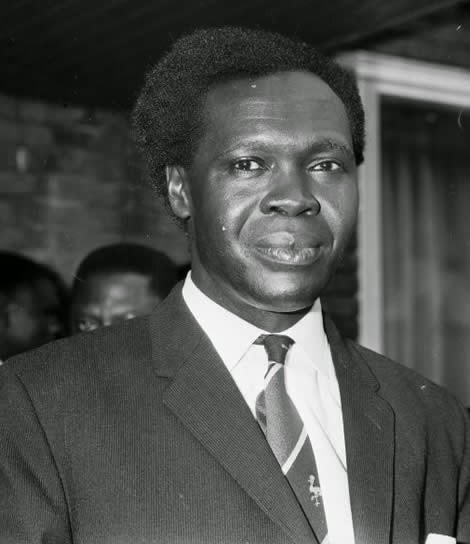

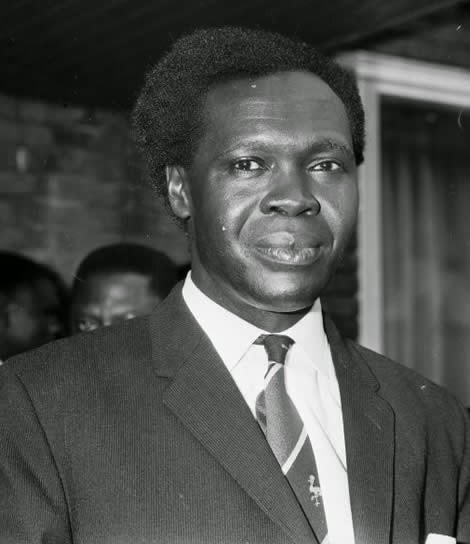

Apollo Milton Obote was prime minister of Uganda from 1962 to 1966 and state president from 1966 to 1971 and again from 1980 to 1985. Although he began his adult life as a schoolteacher, he is best known for leading Uganda to independence on October 9, 1962, in a relatively peaceful revolution. Prior to independence, Obote served on the Ugandan legislative council beginning in 1957, and in 1960 he founded the Ugandan People’s Congress.

Obote created a political coalition with his rival, Sir Edward Mutesa, king of Buganda, in preparation for the peaceful handover of colonial power to indigenous black African rule. Obote used the position of his rival political leader to gain political favor in the region of Buganda. In a practical political move, Mutesa was installed as president with Obote as prime minister.

As prime minister, Obote held formal state power in his hands. His nominally socialist rule after independence made him unpopular with Western states, particularly Britain. While the country was peaceful and economically stable, the period immediately following independence in Uganda was a difficult time for both Mutesa’s presidency and Obote’s prime ministership.

At the time of independence, Uganda was the only peaceful nation in the region and it become a safe haven for refugees from Zaïre, Sudan, and Rwanda. This placed a huge drain on Uganda’s scarce resources and economy.

|

| Sir Edward Mutesa, first president of Uganda |

This period also made it clear that Obote was not going to share power with coalition president Mutesa. This made confrontation inevitable. The trigger for confrontation was Obote’s indictment in a gold-smuggling plot with Idi Amin, then deputy of the Ugandan Armed Forces.

Instead of complying with President Mutesa’s investigations, Obote suspended the Ugandan constitution under the power of his prime ministership, abolishing the role of the leaders of Uganda’s five tribal kingdoms, removing power from Mutesa, and giving himself unlimited emergency powers. The corrupt Ugandan judiciary cleared Obote of all charges of gold smuggling.

The incident, however, incited Obote and his supporters to stage a coup against Mutesa in 1966. He then had himself installed as president on March 2. Obote’s first act as president was to have his attorney general, Godfrey Binaisa, rewrite the Ugandan constitution, transfer all powers to Obote’s presidency, and nationalize all foreign assets.

Obote’s first presidency did not last long. In 1971 Obote was disposed by his army chief, Idi Amin, who had assisted him in overthrowing Mutesa fewer than 10 years prior. Obote fled to Tanzania with many of his supporters. After nine years in exile, Obote gathered Ugandan exiles in Tanzania and ousted Amin in 1979.

In an attempt finally to gain Western support for his second presidency, Obote ordered that Uganda be ruled by a presidential commission before democratic elections were to be held in 1980. Although Obote won the 1980 elections, his second rule was marked by civil war, further distancing him from Western approval.

|

Apollo Milton Obote was prime minister of Uganda from 1962 to 1966

and state president from 1966 to 1971 and again from 1980 to 1985 |

Believing the 1980 elections to be rigged, the opposition parties staged a guerrilla rebellion under Yoweri Museveni’s National Resistance Army. Obote was deposed in July 1985, again by his own army commander, Bazilio Okello, and General Tito Okello in a military coup. This time Obote fled to Zambia. Obote remained in southern Africa until his death on October 10, 2005, of kidney failure at a hospital in Johannesburg, South Africa.

Idi Amin is perhaps best known for ousting his predecessor, Apollo Milton Obote, and for instituting a totalitarian regime that would devastate Uganda both politically and economically. Amin’s rise to power began in January 1971, when President Obote headed off to the Commonwealth Heads of Government meetings in

Singapore.

Suspecting trouble, Obote left his staff with the order to have Idi Amin and his supporters arrested upon his departure. On the morning of January 25, 1971, forces loyal to Idi Amin stormed strategic military targets in Kampala and the airport in Entebbe.

The first shells fired at Entebbe Airport killed two Roman Catholic priests, setting off a wave of violence throughout the country. Despite the initial disorganization on the part of Amin and his troops, they managed to carry out mass executions of pro-Obote troops and supporters. Obote chose exile in Tanzania.

Military Dictatorship  |

| Idi Amin was the third President of Uganda, ruling from 1971 to 1979 |

After assuming power, Idi Amin repudiated Obote’s soft socialist foreign policy, resulting in Uganda’s recognition by Israel, Britain, and the United States. However, many African nations and organizations, including the Organization of African Unity, refused to recognize Idi Amin and his military government.

Nevertheless, Idi Amin embraced the label "totalitarian" and renamed the government house the Command House, later instituting an advisory defense council composed of military commanders.

In an attempt to place Uganda under his military dictatorship, he extended military rule to his cabinet members, who, if not drawn from the military, were advised that they would be subjected to military discipline. Army commanders, with Amin’s blessing, acted like warlords, representing the coercive arm of the government.

Foreign policy was revised again in 1972 so that the country could obtain financial assistance and technical support from Libya. In doing so, Amin expelled all remaining Israeli advisers and became anti-Israeli in accordance with Libyan policy.

Idi Amin went in search of foreign help in the form of monetary aid from Saudi Arabia. In doing so, Amin rediscovered Uganda’s previously neglected Islamic heritage. In attempts to recoup profits from lost Western foreign aide, Amin went on to expel the Asian minority in Uganda and seize their property.

However, this appropriation proved disastrous for the already failing Ugandan economy, which was fueled by export crops. Yet the money from the sale of export crops was being recycled back into the purchase of imports for the army.

As a result, rural farmers turned to smuggling from neighboring countries. This became an obsession for Idi Amin toward the end of his rule. He went on to appoint his mercenary adviser, British citizen Bob Astles, to take all necessary steps to end the problem.

The end of Amin’s rule also faced another problem—a counterattack from former Ugandan leader Obote. Idi Amin feared this with good reason. Shortly after Idi Amin expelled the Asian minority in 1972, Obote did attempt an attack into southern parts of Uganda.

Although the attack was launched by a small contingent of only 27 army trucks, his ambition was to capture the strategic military post of Masaka near the border. Obote’s troops decided to settle in and wait for a general uprising against Amin, which did not occur.

|

| Map of Uganda |

Obote also attempted a seizure of Entebbe Airport by allegedly hijacking an East African Airways flight out of Tanzania. The attempt failed to accomplish much when the pilot blew out the tires on the passenger plane, and the flight remained in Tanzania.

Amin is internationally known for the hostage crisis at Entebbe Airport in June 1976, when Amin offered Palestinian hijackers of an Air France jet from Tel Aviv a protected base from which they could press their demands in exchange for the release of Israeli hostages.

The dramatic rescue of the hostages by Israeli commandos was a severe blow to Amin. Amin’s rule is also marked by a number of disappearances of priests and ministers in the 1970s. The matter reached a climax with the formal protest against army terrorism and death squad activity in 1977 by Church of Uganda ministers, led by Archbishop Janani Luwum.

In response to Luwum’s outspoken agenda against Amin’s violent domestic policies, it appears that Idi Amin had Luwum assassinated. Although Luwum’s body was recovered from a clumsily contrived "auto accident", subsequent investigations revealed that Luwum had been shot by Amin himself.

This last in a long line of atrocities was greeted with international condemnation, but apart from the continued trade boycott initiated by the United States in July 1978, lisan condemnation was not accompanied by action.

Idi Amin went on to claim that Tanzanian president

Julius Nyerere—his perennial enemy, partially due to Nyerere’s acceptance of Obote after the coup—had been at the root of his troubles. Amin accused Nyerere of waging war against Uganda. Idi Amin invaded Tanzanian territory and formally annexed a section across the Kagera River boundary on November 1, 1978.

Declaring a formal state of war against Uganda, Nyerere mobilized his citizen army reserves and counter-attacked, joined by Ugandan exiles united as the Uganda National Liberation Army (UNLA). The Ugandan Army retreated steadily. Libya’s

Muammar Qaddafi sent 3,000 troops to aid fellow Muslim Idi Amin, but the Libyans soon found themselves on the front line.

Tanzanian troops and the UNLA took Kampala in April 1979, aided by Obote, and Amin fled by air, first to Libya and later into permanent exile in Jiddah,

Saudi Arabia, where he died on August 16, 2003, after being in a coma for over a month. The current president of Uganda is Yoweri Museveni, who was elected in February 2006.

|

| Scenery around Kibale Forest in Kibale National Park, Uganda |