|

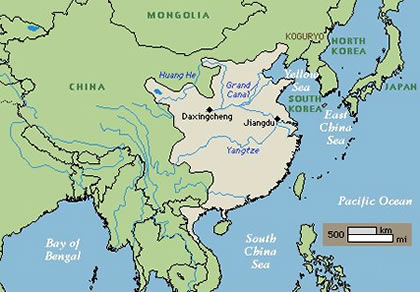

| Ming dynasty map |

The Ming dynasty, which spanned 1368–1644, can be divided into two segments. The first part, between 1368 and c. 1450, was a period of great achievement, growth, stability, and prosperity; the latter part, from c. 1450 to 1644, was characterized by weak and unstable rulers, corruption, and abuse of power that culminated in rebellions and overthrow.

The Ming dynasty has an important place in Chinese history because of its longevity and rule over unified China, and because it was the last Chinese imperial dynasty not founded and ruled by peoples of nomadic origin.

Ming Taizu (T’ai-Tsu) China was in ruins by the mid-1300s under the Mongol

Yuan dynasty (1279–1368). It suffered from a collapsing economy, wrecked by financial mismanagement, runaway inflation, natural disasters, famine, and plague. Numerous rebel movements rose to topple the Yuan dynasty, among them one led by an impoverished peasant named Zhu Yuanzhang (Chu Yuan-chang).

Zhu focused on consolidating his power in the Yangzi (Yangtze) River valley in southern China, establishing his capital in

Nanjing (Nanking), a city rich with historic significance, from which he invaded the north, sending the last Yuan emperor in flight to Mongolia in 1368.

It was the second time in Chinese history that a commoner had ascended the throne (the first was

Liu Bang, who founded the Han dynasty in 202 b.c.e.). He chose the dynastic name Ming, which means “brilliant.”

He reigned for 30 years (1368–98), chose for himself the reign title Hongwu (Hung-wu), which means “bounteous warrior,” and is also known by his posthumous title Taizu, which means “Grand Progenitor.” He and his immediate successors worked to restore Chinese prosperity and prestige after the humiliation and exploitation of Mongol rule.

|

| Ming Taizu (T’ai-Tsu) |

Emperor Hongwu’s policies put his stamp on the dynasty. He restored the economy by freeing people enslaved by Mongols and resettling them on ravaged lands, especially in northern China. He gave tax breaks to the peasants, repaired

irrigation works, rebuilt granaries, and adopted a tax policy that favored the poor.

He gave much authority to localities for maintaining law and order by organizing them into the baojia (paochia) system: 10 families formed a jia under a leader and were responsible for each other, and 10 jia formed a bao in which 100 families were responsible for each other. This system of local

organization persisted in China into modern times.

Confucian Education  |

| Confucian Education |

Hongwu ordered the founding of schools throughout the empire, based the curriculum on Confucian teachings, and reinstated the examination system to recruit officials. His son the emperor Yongle (Yung-lo) followed up on this by ordering the foremost scholars to compile an official version of the

Confucian classics and commentaries to guide students in their studies.

In 1415 The Great Compendium of the Five Classics and the Four Books was published, followed by the publication of The Great Compendium of the Philosophy of Human Nature in 1417.

These works reflected the officially accepted Neo-Confucian philosophy as interpreted by the Song philosopher

Zhu Xi (Chu Hsi) and became textbooks in schools in China, Korea, and Japan. Another major contribution to learning was the Yongle Dadian (Yung-lo ta-tien) or Great Literary Repository of the Yongle Reign.

It contained 22,277 volumes, whose index alone ran to 60 volumes. Too large to be printed, it was preserved in manuscript sets in imperial libraries. Such great government-sponsored works reflected and resulted in huge national interest in

learning, which made the Ming a great period in human history. Economic prosperity permitted wider and growing literacy, from which the printing industry also benefited.

Defense Against the Mongols Emperor Hongwu established a highly centralized administrative system that combined features from the previous

Tang (T’ang) dynasty, Song dynasty, as well as the Yuan dynasty. But he abolished the position of chief minister, so that the autocratic ruler held all the reins of power.

Recognizing that abuse of power by eunuchs contributed to the decline and fall of earlier dynasties, he forbade eunuchs to interfere in government. He established a million-man professional standing army that was hereditary.

He gave governmen towned land to each garrison, requiring the soldiers to till the land in their spare time so that they would not be a burden on the treasury. This did not work in practice and the treasury had to allocate funds to the army regularly.

The army units were rotated in guarding the capital region,

the Great Wall, and at strategic locations throughout the empire and were trained by special tactical officers. The division of authority between garrison commanders and tactical commanders prevented the development of warlordism and precluded revolts by the army during the dynasty.

Reflecting the deep resentment most Chinese felt toward Mongols, he forbade Mongol dress and customs among Chinese and ordered those Mongols remaining in China to adopt Chinese names and to become assimilated.

Emperor Hongwu, his sons, and generals led campaigns that drove remnant Mongols to the Lake Baikal region in present-day Russia. They also regained all Chinese lands including modern Manchuria, Inner Mongolia, Yunnan, Sichuan (Szechwan), and Xinjiang (Sinkiang) and accepted the vassalage of Korea, Vietnam, and Central Asian states.

Emperor Yongle (Yung-Lo)  |

| Emperor Yongle (Yung-Lo) |

Hongwu left the throne to his young grandson, who was, however, ousted by his uncle the prince of Yan (Yen), fourth son of Hongwu. After a civil war that lasted between 1399 and 1402 and ended with the burning of the palace in Nanjing it was presumed that the young emperor and his family had died.

The victorious prince of Yan became the emperor Yongle (Yung-lo), r. 1402–24. Yongle is also known by his posthumous title Chengzu (Ch’eng-tsu), “successful progenitor,” and is sometimes called the second founder of the Ming dynasty.

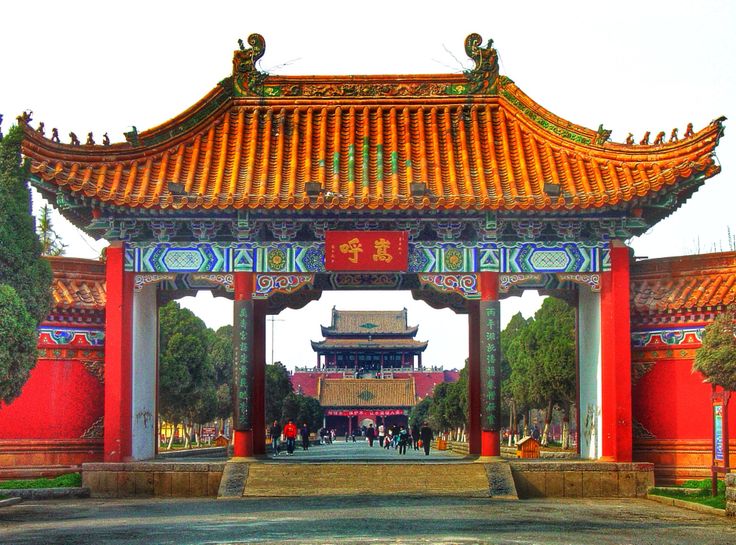

He moved the national capital to Beijing (Peking) in 1421, after rebuilding it from the ruined Yuan capital Dadu (Ta-tu); the palaces, temples, and city walls of that city date to his reign. He had repaired the silted up Grand Canal to connect to Beijing to bring supplies from the south to the capital.

A seasoned general, he personally led five campaigns into Mongolia to prevent the resurgence of Mongol power. Another Ming army intervened in

Vietnam in 1404, annexing that area to the Ming Empire. However Vietnam regained its autonomy after 20 years and became a Ming vassal state.

Troubled by Japanese pirates he intimidated the shogun of Japan into accepting vassalage for the first time in history. Yongle was also famous for authorizing huge armadas to show the flag, promote trade, and enroll vassal states across Southeast Asia, the Indian Ocean, to as far as the northeastern coast of Africa.

The eunuch admiral

Zheng He (Cheng Ho) commanded seven expeditions (the last one set out after Yongle had died). In appointing Zheng He and other eunuchs to high positions Yongle violated his father’s strong injunction.

Although he kept them under firm control, later weak Ming rulers would rely on them for advice, undermining the bureaucracy and resulting in corruption and abuse of power, with disastrous effects.

For example, in 1449 a weakling emperor appointed his favorite eunuch commanding officer, and together they went to war against a Mongol chief, only to suffer defeat and capture, throwing the government into chaos in the process.

China Recovers Government policies that favored land reclamation and economic activities resulted in growing prosperity, and the gradual repopulation of northern China and migration to the south and southwest, driving aboriginal peoples to remote mountainous regions.

Production of silk was encouraged and became widespread in areas south of the Yangzi River. Women and girls were in charge of growing mulberry trees and tending silkworms and also worked in silk weaving factories, bringing additional income to farm families.

The cultivation of cotton and manufacture of cotton cloths also expanded during the Ming, providing clothes for ordinary people. Crafts also flourished, with metal, lacquer, and paper industries leading the way. True porcelains were first made in China during the

Song dynasty, hence the name china.

Its manufacture continued to advance during the Yuan, but it was under the Ming that Chinese porcelain manufacture reached its apogee. Under state encouragement, Jingdezhen (Ching-te-chen), the porcelain manufacturing center, had 3,000 government and privately owned factories.

Four emperors followed Yongle up to 1450. They and most subsequent Ming rulers were mediocre; many were also eccentric. They abandoned the militant foreign policy of the dynastic founders and resorted to defensive tactics, mainly reflected in rebuilding the Great Wall into the formidable monument that survives to the present. Although later Ming lost its earlier dynamism, the institutions and policies set by the dynastic founders worked to continue its survival until 1644.