The history of the first crusading kingdom of Jerusalem commences with the conquest of Jerusalem by the Christian army, led by

Godfrey of Bouillon, duke of Lower Lorraine, on July 15, 1099. The crusading host stormed the city and, having slaughtered the native population, captured the Church of the Holy Sepulcher.

Although the religious mission was accomplished, the political goals of the crusading leaders were yet to be achieved. Following Jerusalem, other towns fell to the crusaders: Haifa in 1100, Arsuf and Caesarea in 1101, Acre in 1104, Sidon in 1110, Tyre in 1124, and finally, Ascalon in 1153. At the same time the crusading leaders established their control over some trans-Jordan areas, as well as by the northern coast of the Red Sea.

Godfrey of Bouillon never assumed the title of the king, addressing himself merely as a “defender of the Holy Sepulcher.” He died childless on July 18, 1100, and on Christmas Day of the same year, his brother Baldwin of Boulogne was crowned as Baldwin I.

It was under him that the crusading army captured most of the aforementioned towns. He died on April 2, 1118, and the kingship passed to the hands of his cousin, Baldwin of Bourcq, crowned as Baldwin II (1118–31). Upon his death, his son-in-law, Fulk, count of Anjou, succeeded the crown.

His reign (1131–43) is characterized by political and social unrest in the kingdom, which was divided between the “king’s party” supporting Fulk and the “queen’s party” following his wife, Melisende. With Fulk dead, Melisende attempted to rule on her own, provoking anger of her young son, Baldwin III (1143–63), and his supporters. The latter forced the queen to give up her intention. Among Baldwin III’s achievements were the conquest of Ascalon (1153) and rebuilding of the Church of the Holy Sepulcher (completed in 1149).

His younger brother Amalric (1163–74) initiated three Egyptian campaigns against Nur al-Din, capturing Bilbais on November 1168. Amalric’s son Baldwin IV the “Leper” (1174–85) was surrounded by court intrigues and conspiracies. At the center of these intrigues stood Baldwin’s sister Sibylle with her second husband, Guy of Lusignan, and Raymond III, count of Tripoli.

Baldwin died in May 1185, leaving the Crown to Sibylle’s son Baldwin V, still a boy. The latter died on September 13, 1186, and Sibylle was crowned with Guy, who was captured by the Muslim leader

Saladin (Salah ad din, Yusuf), in the

Battle of Hattin (July 4, 1187).

Despite their political control over vast territories, the crusading kings could never achieve continual peace and their rule was permanently threatened by the Muslim enemies, as well as their Christian rivals—Frankish nobility.

The Islamic threat became evident with the conquest of Edessa in 1144 by a Muslim warlord Zangi, while the crusaders’ weakness was proved by inability of the Christian forces to cope with the Muslim army, which eventually captured Damascus on April 25, 1154. The failure in the north was followed by a similar failure in the south: a new Muslim leader, Salah ad Din, also known as Saladin, (1138–93), repelled the crusading forces in 1169 in Damietta, and 1174 in Alexandria.

Having subdued his Muslim rivals between 1174 and 1186, Saladin moved on the attack against the Christians. On July 4, 1187, he defeated the crusading army led by King Guy in the Battle of Hattin, leaving the rest of the Christian towns exposed to his threat. Acre was captured on July 10, 1187, while Jerusalem capitulated on October 2 of the same year. The first crusading kingdom came to its end.

The Second Crusading Kingdom of Acre (1189–1291) The disaster of Hittin and fall of Jerusalem provoked a strong reaction in western Europe, whose leaders rose to a new crusade. Led by

Richard I the Lionheart of England,

Philip II Augustus of France, and

Frederick I Barbarossa, the German emperor who died on his way to the Holy Land, the crusading host had arrived before the walls of Acre in the summer of 1189. After two years of siege the city was recaptured on July 12, 1191.

The Christian unity did not last long; Philip Augustus decided to return to France, while Richard remained in Palestine. He failed to capture Jerusalem and on September 2, 1192, the Christian and Muslim armies came to a settlement. The coastline stretching between Jaffa and Tyre came into the hands of the crusaders, while Jerusalem remained under Muslim control, with holy sites accessible to pilgrims.

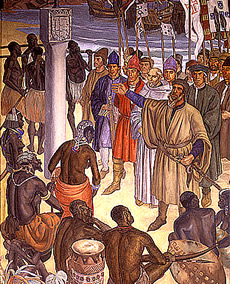

Acre effectively became not only a political capital of the new crusading kingdom, but also its cultural and economic center. The city was strongly multicultural in character, being home to Italian, French, English, German, Greek, Muslim, Jewish, and Eastern Christian communities.

The struggle with the Muslims resumed in 1219, when John of Brienne, king of Jerusalem, and his army penetrated into Egypt, capturing Damietta. From there they moved to Cairo, which they failed to reach, having suffered a defeat at the hands of the Ayyubid sultan al-Kamil (1218–38) on August 30, 1221, near al-Mansura. The crusaders’ lives were spared in exchange for Damietta.

The next crusading initiative came from the German emperor Frederick II (1212–50), who came to Palestine in September 1228 with a large army. Fearing Frederick’s military advantage, al-Kamil offered a treaty, which granted the crusaders Jerusalem, Galilee, and part of Sidon and Toron.

Jerusalem remained in Christian hands until 1239, when the Ayyubids briefly captured it, only to be restored to the Christians in 1240. The Christian rule of Jerusalem came to its end four years later, with the conquest by the Khorezmian Turks in the summer of 1244.

The crusade of

Louis IX of France (1229–70) did not aim at the reconquest of the Holy City. On June 6, 1249, his forces seized Damietta and moved on to Cairo, only to suffer the fate of their predecessors of 1221. On April 6, 1250, his army was badly beaten at al-Mansura and as the result the king and his men were taken captive.

The Latin population of Acre did not always live in peace. The tensions were especially apparent between the Venetian and Genoese communities, who struggled over commercial supremacy in the region. The War of St. Sabas broke out in 1256 and lasted until the Genoese defeat in 1258. Following the defeat the Genoese were forced to leave the city and their territory was overrun by the Venetians.

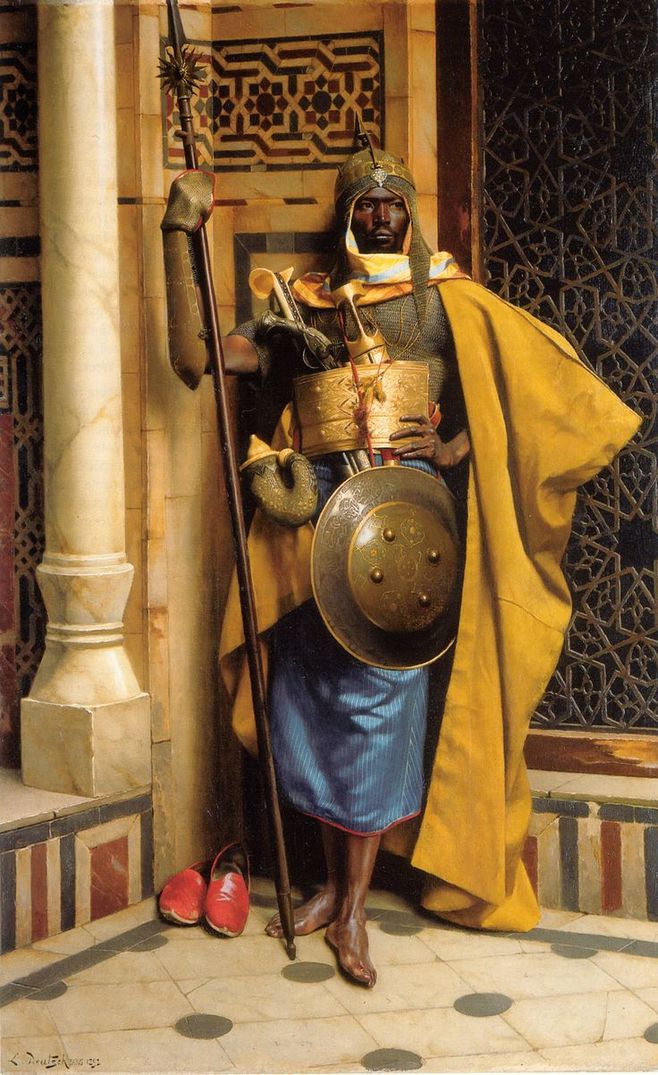

In the meantime a new threat had emerged from the Mamluks, who in 1250 overthrew the Ayyubid Sultanate in Egypt and established their own military rule. Faced with the crusading presence and the Mongol threat, under Sultan Baybars (1260–77) and his heirs, the Mamluks conquered the remaining towns, villages, and forts of the crusading kingdom, forcing its inhabitants into exile.

The European

population of the Outremer sharply fell, resulting in the inability of the crusaders to stop the Mamluks, and led to the simpulan fall of the kingdom. On May 18, 1291, the inhabitants of Acre, the capital town of the kingdom, surrendered and those not slain by the conquerors returned to Europe, mainly France and Italy. The town was laid to waste and remained so until it was rebuilt in the 18th century. The history of the Latin kingdom in the Holy Land came to an end.

Minor Crusading States The conquest of Jerusalem on July 15, 1099, may signify the establishment of the first crusading kingdom, but not the first crusading state. As early as March 1098, Baldwin of Boulogne, the future king Baldwin I of Jerusalem (1100–18), forced the Armenian principality of Edessa to accept him as its new master. Baldwin assumed the title of count of Edessa, establishing the first Latin principality in the Near East.

Two years later upon the death of his brother Godfrey of Bouillon (July 18, 1100), the first ruler of the kingdom of Jerusalem, Baldwin changed his title to king of Jerusalem. Baldwin of Bourcq was also crowned as Baldwin II of Jerusalem (1118–31). While Baldwin II exercised full control over both the kingdom of Jerusalem and the county of Edessa, his successor handed the lordship of Edessa to the hands of the family of Courtenay.

The first count of the Courtenay dynasty was Joscelin I (1119–31), who was succeeded by Joscelin II (1131–49). It was under the latter that the Muslim leader Zangi captured the principal town Edessa in 1144 and forced the Christian ruler and his family to desert it. Zangi killed the male Christian population of the city, reduced the women and children into slavery, and decimated the city in 1146.

Joscelin moved to Turbessel, where he had established his power, only to be captured by the Turkish sultan of Konya, Masud, in 1149. The latter handed Joscelin over to Nur al-Din, who took him captive to Aleppo, where the count died in prison in 1159. His wife, Beatrice, granted the remains of the county to the Byzantine emperor. The son of Joscelin and Beatrice, Joscelin III, retained the title, without ever ruling the county.

The history of the county of Tripoli goes back to 1102, when Raymond of Saint-Gilles, a crusading leader, named himself as count of Tripoli. He did not live to capture the town itself, which surrendered in July 1109. A struggle between Raymond’s cousin William Jordan of Cerdagne and his eldest son, Bertrand, followed the conquest of the town.

The rivalry ended thanks to the intervention of Baldwin I of Jerusalem, who installed Bertrand as his vassal. The latter died in 1112 and soon after, the county passed to his young son, Pons, who attempted to set himself free from the authority of Baldwin II, his suzerain.

Pons’s rebellion was crushed in 1122, although he retained his county. He ruled until 1137 when the townsfolk of Damascus killed him. His successor, Raymond II, faced a political challenge from Bertrand, the illegitimate son of Alfonso Jordan, son of Raymond of Saint-Gilles. He eventually overcame his challenge with the aid of Nur al-Din.

After his murder by the Assassins in 1152, the rule passed to his son, Raymond III (1152–89). In 1164 he was captured and imprisoned by Nur al-Din, while on a campaign to relieve the siege of Harim, along with Bohemond III of Antioch and Joscelin III of Edessa. During their imprisonment, Amalric of Jerusalem was regent of the county. Raymond III was released in 1172 and two years later rose to the position of regent of Jerusalem.

He died in Tyre in 1187, having installed his godson, Bohemond IV, prince of Antioch, as his successor. The two baronies were united, with a brief exception of the years 1216–19, until the fall of Antioch in 1268. After the death of Count Bohemond VII in 1287, the county sank into political and social chaos, which was exploited by the Mamluk sultan Qalawun. The city fell into his hands in 1289, after a siege.

The origins of the principality of Antioch go back to the conquest of the city in 1098 by Bohemond of Taranto, the first prince of Antioch. The latter died in 1103 leaving the principality to his young son, Bohemond II, while Tancred of Hauteville and Roger of Salerno acted, respectively, as his regent until 1119.

In October 1126 Bohemond was married to Alice, daughter of Baldwin II, king of Jerusalem (1118–31). The union of two crusading families did not last long: His Muslim enemies killed Bohemond in February 1130. Bohemond left a young daughter, Constance, whose regent was Raymond of Poitiers.

In 1136 Raymond had officially assumed the title of the prince of Antioch and remained in power until his death in the battlefield on June 29, 1149. During his rule, the Byzantine emperor John Komnenus invaded Antioch in 1137 and captured towns that threatened the principality. The campaign was repeated in 1142 and the integration of the principality into the empire was hindered only by John’s death in 1143.

In 1153 Constance married Renaud of Châtillon- sur-Loing, a man of well-established knightly family, who was taken captive by his Frankish enemies in 1161. As a result, the magnates of Antioch forced Constance to hand the title of the prince to her son, Bohemond III.

The latter joined Raymond III, count of Tripoli, in a military campaign against Nur al-Din. The result of this campaign was a complete defeat of the Christian army in 1164. According to the Muslim sources, Nur al-Din was advised to capture Antioch, which he did not do. Raymond was ransomed by the emperor and restored to the principality.

However, the real ruler of Antioch was King Amalric of Jerusalem. In the course of Saladin’s campaigns of 1280–90, the territory of the principality had been reduced to the surroundings of the town of Antioch. The Armenian prince Leo exploited the weakness of Bohemond III, attempting to capture the city. The local population in 1194, however, drove out his army.

Upon Bohemond’s death in April 1201, his older son Bohemond IV succeeded him, also reigning as count of Tripoli, being adopted by Raymond III of Tripoli. The two Latin baronies were united under one prince. Unlike the kingdom of Jerusalem, Antioch survived the assault of Saladin, with the assistance of the Italian city-states, but afterward did not play any important role in the subsequent Crusades.

After Bohemond IV’s death in 1201, the principality was torn by a power struggle between the two rivals, Bohemond of Tripoli, the future Bohemond V (1207–23), and Raymond-Ruben of Armenia, Bohemond III’s grandson. The struggle between Antioch and Armenia ended with the marriage of Bohemond VI and an Armenian princess, Sybille. The city and the entire principality fell to the Mamluks in 1268. The title prince of Antioch passed to the king of Cyprus, after the fall of Acre in 1291.

Although not European countries, the Latin states of the Near East played an important role in the political, social, economic, and cultural life of Europe in the High Middle Ages. The very idea of the crusading knight became the ideal of the European nobility.

The encounter with the Orient and its culture, different from that of the West, had enriched the horizons of the Europeans. The Outremer states, at times through the mediation of Italian city-states, maintained vital mercantile connections with Europe, acting as the supplier of African gold and spices.