|

| Abbasid caliphate greatest extent |

The Abbasids defeated the Umayyads to claim the caliphate and leadership of the Muslim world in 750. The Abbasids based their legitimacy as rulers on their descent from the prophet Muhammad’s extended family, not as with some Shi’i directly through the line of Ali and his sons.

The Abbasids attempted to reunify Muslims under the banner of the Prophet’s family. Many Abbasid supporters came from Khurasan in eastern Iran. Following the Arab conquest of the Sassanid Empire, a large number of Arab settlers had moved into Khurasan and had integrated with the local population. Consequently, many Abbasids spoke Persian but were of Arab ethnicity.

The New Capital of Baghdad

The first Abbasid caliph, Abu al-Abbas (r. 749–754), took the title of al-Saffah. His brother and successor, Abu Jafar, adopted the name al-Mansur (Rendered Victorious) and moved the caliphate to his new capital, Baghdad, on the Tigris River. Under the Abbasids the center of power for the Muslim world shifted eastward with an increase of Persian and, subsequently, Turkish influences.

Persian influences were especially notable in new social customs and the lifestyle of the court, but Arabic remained the language of government and religion. Thus, while non-Arabs became more prominent in government, the Arabization, especially in language, of the empire increased.

Mansur’s new capital, built between 762 and 766, was originally a circular fortress, and it became the center of Arab-Islamic civilization during what has been called the golden age of Islam (763–809). With its easy access to major trade routes, river transport, and agricultural goods (especially grains and dates) from the Fertile Crescent, Baghdad prospered. Agricultural productivity was expanded with an efficient canal system in Iraq.

Commerce flourished with trade along well-established routes from India to Spain and trans-Saharan routes. A banking and bookkeeping system with letters of credit facilitated trade. The production of textiles, papermaking, metalwork, ceramics, armaments, soap, and inlaid wood goods was encouraged. An extensive postal system and network of government spies were also established.

Harun Al-Rashid and the Abbasid Zenith

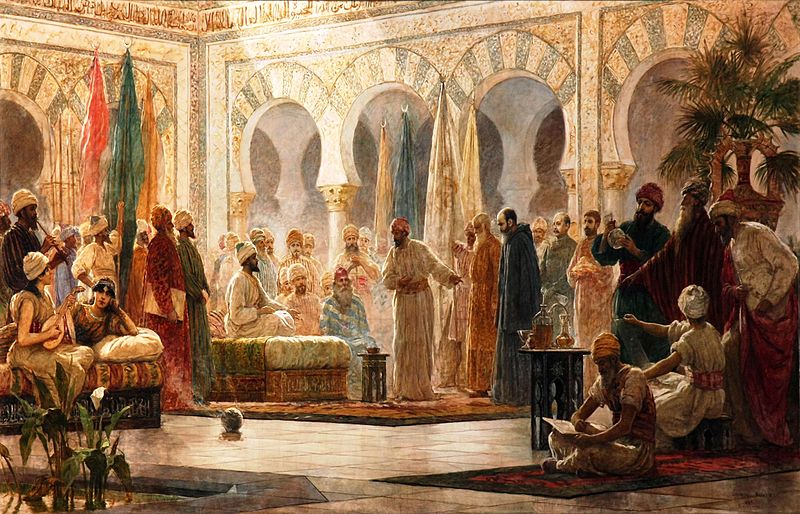

|

| Harun Al-Rashid |

The zenith of Abbasid power came under the caliphate of Harun al-Rashid (r. 786–809). Harun al-Rashid, his wife Zubaida, and mother Khaizuran were powerful political figures. Zubaida and Khaizuran were wealthy and influential women and both controlled vast estates. They also played key roles in determining succession to the caliphate.

Like the Umayyads, the Abbasids never solved the dilema of succession, and their government was weakened and ultimately, in part, destroyed because of rivalries over succession. Under Harun al-Rashid the Barmakid family exerted considerable political power as viziers (ministers to the ruler).

The Barmakids were originally from Khurasan and had begun serving the court as tutors to Harun al-Rashid. The Barmakids served as competent and powerful officials until their fall from favor in 803, by which time a number of bureaucrats and court officials had achieved positions of considerable authority.

The wealth of the Abbasid court attracted foreign envoys and visitors who marveled over the lavish lifestyles of court officials and the magnificence of Baghdad. Timurlane destroyed most of the greatest Abbasid monuments in the capital, and Baghdad never really recovered from the destruction inflicted by him.

Under the Abbasids, provinces initially enjoyed a fair amount of autonomy; however, a more centralized system of finances and judiciary were implemented. Local governors were appointed for Khurasan and soldiers from Khurasan made up a large part of the court bodyguard and army.

In spite of their power and wealth the Abbasids twice failed to take Constantinople. The Abbasids also had to grapple with ongoing struggles between those who wanted a government based on religion, and those who favored secular government.

Civil War Over Accession and the End of the Abbasids

Harun al-Rashid’s death incited a civil war over accession that lasted from 809 to 833. During the war, Baghdad was besieged for one year and was fought for by the common people, not the elite, in the city. Their exploits were commemorated in a body of poetry that survives until the present day.

The attackers finally won and the new Caliph Mutasim (r. 833–842) moved the capital to Samarra north of Baghdad in 833. During the ninth century the Abbasid army came to rely more and more on Turkish soldiers, some of whom were slaves while others were free men. A military caste separate from the rest of the population gradually developed.

In Khurasan, the Tahirids did not establish an independent dynasty but moved the province in the direction of a separate Iranian government. As various members of the Abbasid family fought one another over the caliphate, rulers in Egypt (the Tulunids), provincial governors, and tribal leaders took advantage of the growing disarray and sometimes anarchy within the central government at Samarra to extend heir own power.

The Zanj rebellion around Basra in southern Iraq in 869 was a major threat to Abbasid authority. The Zanj were African slaves who had been used as plantation workers in southern Iraq, the only instance of largescale slave labor for agriculture in the Islamic world.

Other non-slave workers joined the rebellion led by Ali ibn Muhammad. Ali ibn Muhammad was killed fighting in 883 and the able Abbasid military commander, Abu Ahmad al-Muwaffaq, whose brother served as caliph, finally succeeded in crushing the rebellion.

Under Caliph al-Muqtadir (r. 908–932) the capital was returned to Baghdad where it remained until the collapse of the Abbasid dynasty. By the 10th century any aspirant to the caliphate needed the assistance of the military to obtain the throne. The army became the arbiters of power and the caliphs were mere ciphers. A series of inept rulers led to widespread rebellions and declining revenues while the costs of maintaining the increasingly Turkish army remained high.

By the time the dynasty finally collapsed, it was virtually bankrupt. In 945 a Shi’i Persian, Ahmad ibn Buya, took Baghdad and established the Buyid dynasty that was a federation of political units ruled by various family members. A remnant of the Abbasid family, carrying the title of caliph, moved to Cairo where it was welcomed as an exile with no authority over either religious or political life.